HISTORY OF THE THURSO AND NATION VALLEY RAILWAY

Inception

Construction 1925 - 1940

The War Years

Post War Extension

Road Competition

Closure

Inception

St. Patrick's Day in 1921 was important

for the small village of Thurso on

the Québec side of the Ottawa River, 30 miles east of Ottawa.

However,

not everybody in this 600 strong predominantly French Canadian

community

celebrated the greatest of Irish occasions. There were mixed feelings

in

the farmsteads north of Thurso because, on March 17, 1921, Paul

Bourget,

then of the Anglin Norcross Company, set out with a survey crew to look

for

a favourable location for a railway. This would run from the valley of

the

Rivière La Blanche, to the south of the village of Ste-Sixte,

and

then to Thurso. Snow was still on the ground and would remain for at

least

another five or six weeks, but travel in the bush was easier than when

the

underbrush had leafed out and the cool weather was definitely

preferable

to the mosquitoes and black flies that make summer days miserable.

The Singer Company, famous for industrial and domestic sewing machines, was founded in Boston, Mass. in 1850. It had opened its first Canadian plant in Montreal in 1883 and moved to a larger facility at St-Jean, Québec in 1906. In 1922 the company decided to purchase a timber limit (i.e., license to cut timber on a section of land) and establish a sawmill to use Canadian timber. Previously the company had imported lumber for its cabinets. This led, in 1923, to the $500,000 acquisition from the Gatineau Company of about 500 square miles of forest to the north and northwest of Thurso. This limit, with its southern boundary some 25-30 miles north of Thurso, had not been worked by the seller, who had only bought it the previous year from the W.C. Edwards Company of Ottawa. The latter company had logged the limit for pine and large spruce sawlogs and at the time of its purchase by Singer, the mixed hardwood stand was the only timber of any real value remaining. The area was sparsely populated. The woodlands were used by the native Oeskarini Indians for hunting and trapping. The most well known of these was Canard Blanc (White Duck) who lived on an island in Lac Simon. He trapped in the area to the west and north of what is now Duhamel and his detailed knowledge and understanding of the region was of great value to the railway builders. Canard Blanc is reputed to have lived to be 112 years old. The timber limits north of Thurso comprised mainly mixed forest and the dominant species of tree were yellow birch, hard maple, hemlock and spruce, with varying amounts of beech, basswood and balsam. From the company's viewpoint the yellow birch was the most important, although it had the cutting rights for all species except spruce, balsam, poplar, hemlock and jack pine. Areas containing a high percentage of yellow birch were rare in Canada and this limit was considered to be one of the best. Earlier loggers had floated their harvest down the Petite Nation River through North Nation Mills and Plaisance. Unlike softwood, hardwood will not float, so the river could not be used by the Singer Company which was thus forced to build a railway. In order to gain access to the timber it was planned to build a main line running generally northwards from Thurso through mixed farming country, a distance of approximately 15 miles, then through sparsely settled country for 10 miles and finally into the forest. Before building the railway, the company had to obtain a charter from the provincial government in Québec. This was duly done by Chapter 113, 15 George V, 1925 "An Act to Incorporate the Thurso and Nation Valley Railway". The petitioners who became the first Directors were:

There was an error in the charter as Paul Bourget's middle initial was in fact "B". Sir Douglas Alexander (1864-1949) maintained his links with the railway he helped to create. He was the fifth President of the Singer Company, a position he achieved at the remarkable age of 41. He had been knighted by King George V in 1921 for his services during World War I. He and the other founders would occasionally visit the line in the Private Car no. 27 to stay at Lac Barrière Depot which was accessible from the wye at Lac de la ferme near Duhamel. These fishing trips were very popular with this heavy set, aging gentleman with a white beard. A keen amateur photographer, his favourite headgear was a tam o' shanter acquired during a trip to Scotland. He would often be joined by Mr. Davidson, Paul Bourget and the other co-founders of the line. Click here to see railway instructions for such a trip. The company planned to start cutting the lumber close to Thurso and gradually work northwards, extending the railway at the same time. This explains why the first thirty-four miles were finished within two years while the remaining twenty-two miles took a further twenty years. It was planned that, when the cutting reached the end of the Singer limits, the trees at the southern end would, once again, be ready for harvesting thus ensuring a continuous supply of lumber. The company's successor, MacLaren, started to harvest at the southern limits again in the 1970s. However, sewing machine cabinets are now no longer made from wood while the railway has given way to truck transport. The church has always exercised a strong influence in the lives of French Canadian communities and there would be no exception here. The village of Thurso was strategically placed for the location of the Singer mill but there was intense lobbying from the adjacent communities of Plaisance to the east and Masson to the west, both of which had a history of logging. All three parish priests became involved on behalf of their communities. The struggle revolved around a small parcel of land in Thurso owned by the church and vital for the construction of the mill. The Bishop of Hull was reluctant to sell because it had been donated to the church on condition that it be used for the sole benefit of Roman Catholics. In the end, the Bishop relented and the way was clear for Thurso to be blessed with the mill. But where would the construction workers live while they built the railway and the mill? Thurso was a small village and accommodation was at a premium. Even here the village priest had a solution. One Sunday he climbed into the pulpit and told the older parishioners to go and live in Fassett, a village some fifteen miles to the east. This would leave room in Thurso to accommodate the able bodied men required for the work. P.B. Bourget came to Thurso as an engineer for the Anglin Norcross Company and maintained control over the construction of the railway. He was entrusted with the task of negotiating for the land required for the right of way. He visited all the property owners concerned. The majority of farmers agreed to sell at fair prices but a few made exorbitant demands. Such cases were turned over to the courts, the lands being condemned in accordance with Québec laws relating to such matters. Finally, agreements were made to cover individual cases. Lambert Cavan farmed just to the north of Thurso and opposed the construction of the railway because the proposed route would cut his farm in half. The company had been able to reach agreement with other land owners but Mr. Cavan held out. The route cut other land holdings across the short length of their land and each had accepted one farm crossing at grade and a cattle underpass. However, the proposed route would traverse the Cavan farm lengthways and he held out for two crossings and two underpasses. The bargaining was difficult and took some time. When agreement was finally reached the construction crews were poised ready to enter the land in question. |

Construction 1925 - 1940

Anglin Norcross commenced construction

in the spring of 1925 and within a

few days the quiet life of this part of rural Québec was

transformed by an extremely active group of construction camps housing

some eighty men.

The work was under the general direction of Colonel Elmit, then General

Manager

of the Singer Company, although P.B. Bourget maintained overall

control.

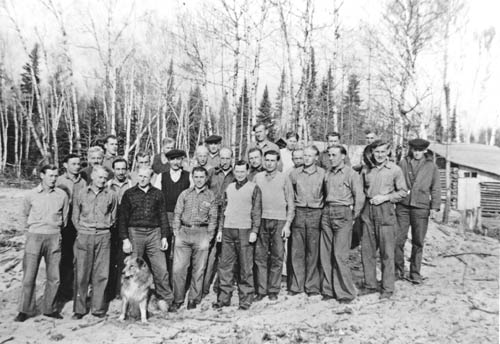

Len Purdy, the railway's first employee, was hired on May 22, 1925 and carried out much of the detailed route location. Surveying parties pushed northward to be followed by blasting squads with tons of dynamite, graders and their numerous teams of horses, bridge builders and finally the supply trains moving cautiously over the newly laid tracks. Problems developed with Ernest Gauthier a land owner at mile 8. He chose a more violent approach as chains were swung around to keep the contractor's people at bay. An uneasy truce prevailed until the forces of law and order could calm things down. At mile 19 a deep valley had to be crossed which involved the construction of a wooden trestle about 60 feet high and 400 feet long. It was built from British Columbia fir at a cost of $25,000 and was known as the "Jasmin Trestle" after the owner of the land over which it was built. The blasting crews made slow progress. Their tedious work of drilling in the solid rock in preparation for the dynamite charges would go on for days with no visible sign of achievement. Then, in a few seconds, all would be changed with a terrific explosion which would knock off the crest of a hill. It was not uncommon in those days to meet a workman with a red flag warning one to keep back because a charge of dynamite was about to be let off. There would follow a loud explosion which must have reminded the many returned soldiers employed on this work of their days in the trenches. On and on these parties progressed, through swamps, diverting streams, building culverts, filling in cuts and blasting off ridges until a fairly level stretch of roadbed had been prepared for ties. The ties were cut by local farmers who hauled them to the roadbed during the preceding winter. The track laying squads started at Thurso where rails were received from the Canadian Pacific Railway in flat cars. Supplies were then forwarded to the construction gangs. It was not long before the line became a regular transportation route for materials of all kinds, and while the railway had not been officially opened for traffic, it was actually doing a lively business. Then followed the hauling and placing of ballast. Fortunately, several good gravel sources were found adjacent to the railway line. A large steam shovel was put to work to load ballast into dump cars, the ballast being hauled out and unloaded where required. Track crews soon had ballast graded and tamped, leaving the line ready for log hauling. It was to be expected that numerous unforeseen obstacles would be encountered in a work of this kind especially when the topography of the land varied from deep valleys to high hills. One of the most difficult problems to overcome was "sink holes" which were usually found in swampy areas. Two of these were discovered several weeks after the rails had been laid and loaded trains had been moving regularly over the track. On one occasion the track sank about four feet while a load of logs was passing over a soft spot. Black muck was pushed up by the downward pressure of the train, leaving the resemblance of a minor earthquake. Fences lining the right of way were pushed sideways as much as four feet by the movement of the soil. It required approximately fifty cars of gravel ballast to stabilize the roadbed at this point. The company rented a small steam locomotive from the Canadian Pacific Railway in the fall of 1925 and the first TNVR locomotive, #1 from the Singer Company in the USA, arrived in late 1925. By the end of 1925 the rail had been ballasted to the village of Ripon and there was skeleton track as far as mile 23. By the end of the 1926 construction season the main line had reached mile 32. The Singer sawmill, power house and lumber drying kilns at Thurso commenced operation the same year, the first logs having been brought down in July. P.B. Bourget was conscious of construction costs and wrote to the Québec government asking for the elimination of the stumpage that was charged for each tie that was used in the construction of the railway. The government compromised and reduced the stumpage from 15 cents to 5 cents per tie. Even at this early stage, Mr. Bourget emphasized that the branch lines he proposed to build were not of a permanent nature but that the ties could be used elsewhere. The TNVR obtained its second steam locomotive in 1927. This was #2, a 2-6-2 tender locomotive built new at the Montreal Locomotive Works. A shop was completed at Thurso by the end of the year to house it. On April 27, 1927 the Singer Company hired Damien Lafleur to oversee the railway. Damien was generally known as "Diamond", the anglicised form of his name. Paul Bourget and Damien Lafleur oversaw the construction, development and operation of the railway for the next thirty years. At mile 26, a construction camp was established which consisted of several frame buildings. These were erected to serve as sleeping quarters for the workmen, to store supplies and to provide dining facilities. The buildings were retained to form the first central point for the woodland operation. It was known as "Headquarters Camp" or "Singer". A small community grew up at Singer which was a convenient location from which to supply the woodland operation. The Company had to provide all the amenities required to support the isolated community including the construction of a school. In 1927 work started on the construction of a branch line westwards from the main line at mile 26, Singer. It took three years to complete the Laroche, or Savanne, branch as follows:  1927 to mile 3 1927 to mile 3  1928 to mile 9 1928 to mile 9  1929 to mile 12 1929 to mile 12This line was not intended as a permanent line and no attempt was made to avoid sharp curves or steep grades. In one instance the grade was 9%, but since this was downhill for the loaded trains, it did not present a serious difficulty. The steepest grade against the load was 3%. Curves were very sharp, several being as much as 40 degrees (143 foot radius). A third locomotive, a three truck Heisler, #3, was purchased in 1929. The slow, geared locomotive was essential to work the steep grades of the Savanne branch and other lines subsequently built into the bush. It spent most of the time in the woods, only coming to Thurso for maintenance. Also in 1929, the company purchased a small Superintendent's car from the Canadian Pacific Railway. Car 27 would outlast the railway. With logs being moved out of the Laroche Valley in 1930, the main line was extended north and west to Lac Iroquois. The last four miles were, in effect, a second branch line from what later became mile 33 on the main line. The first engineering difficulty was encountered at mile 28 at a small lake, known as "Cairo" or "Mulet" Lake, which nestled between two steep hills. This was the only valley through which the line could be routed, and it was planned to blast a ledge along the cliff on the east side of the lake and to dump the loose rock into it so as to form additional width to the shelf for the railway. However, the rocks did not hold as they were dumped into the lake and they slid down to the bottom. Consequently, it became necessary to blast into the side of the cliff several additional feet, which proved to be a most expensive operation. This cut, which was about a quarter of a mile long, was the most expensive blasting job undertaken. The blasting crews spent several weeks drilling for the charges which resulted in an enormous explosion rocking the area for several miles around. During 1931 logs were brought down to Thurso from both the Savanne and Iroquois branches as well as from Baie de l'Ours. A dam was constructed at the foot of Lac Iroquois to raise the water level. This allowed logs to be floated from Lac du Chevreuil across Lac Iroquois to be loaded directly from water to rail cars. Hardwood logs were also floated across the lakes spiked into rafts containing softwood. There was a dramatic downturn in business as a result of the depression and the railway ran at very reduced levels from 1932 to 1935. In spite of the reduced activity, the yard at Thurso was piled high with unsold lumber. The lumber along the Savanne branch had been exhausted and the rails were lifted in 1932 except for the first half mile which was retained as a long tail track to the Singer wye. Meticulous arrangements were made to lift the line. Before the Heisler #3 could be used, Sam Smith took six men to put the line in good enough shape to get the locomotive to the end of the line. Particular attention was paid to the 9% grade at mile 8. Damien Lafleur was in charge of the lifting operation together with engineer Park Smith, fireman Albert Desgagnes, loader P. Danis and a crew of five tongsmen. Click here to see the arrangements made for lifting the Savanne Branch These were hard times. The section crew at Singer was laid off in April 1932 and Damien Lafleur was under severe pressure to reduce his workforce to a minimum consistent with safety. Local farmers took advantage of the light use of the line to use the right of way for hauling with their teams. This damaged the ties and special patrols at irregular intervals had to be set up. One farmer was threatened with a visit to the magistrate at St-Andre Avelin before things could be settled. One happy occasion in an otherwise difficult period was the visit, on June 4, 1936, of Lord Tweedsmuir, the Governor General of Canada. Click here for more details. This

picture was taken on June 4, 1936 and shows the then Governor General,

Lord Tweedsmuir, and his son sitting on a flatcar behind car 27.

This would provide an even better view of the scenery than would car 27

but was not in the plan established by P.B. Bourget, Maybe this

was a last-minute addition for the vice-regal guests. Lawrence W. Hird collection.

By 1938 the Iroquois Branch was exhausted of lumber and the four mile section was lifted that year. In 1939, the Jasmin Trestle, the largest on the line, was filled in with earth to eliminate the expensive maintenance on the trestle. It would otherwise have been a permanent drain on resources. In order to tap new lumber reserves, the TNVR main line was extended five miles north to Duhamel, mile 38, in 1940. This time the effect of improved technology was felt and a D2 trail builder worked alongside a steam shovel. Trucks were used for moving fill in the easier sections. The focus of the woodland operation was moving further north and Duhamel was chosen as the new headquarters. Many items were moved from Singer to Duhamel including the wagon scales in 1942. The Singer school was closed at the end of the 1942 school year and the desks, tables and chairs offered to the Duhamel school board. The bell was returned to Thurso while the building was cut into several sections and moved by rail to Duhamel. A new lodge, known as Lac Barrière Depot, was built just south of Duhamel between Lac de la Ferme and Lac Simon. An earlier lodge, known by the same name, had existed for some time in this area. With the coming of the railway it was felt that more luxurious living quarters were needed. Lac de la ferme was a private lake owned by the Singer Company. |

The War Years

The Second World War began to have an

effect upon the railway in 1940. The

New York purchasing agent of the Singer Company wrote in September

pointing

out that the Canadian government armament purchases were making both

machine

tools and materials difficult to obtain. There was a concerted effort

to

make better use of a wide range of items such as rope, cable, spikes,

nuts

and bolts. A search was made throughout the limits that previously had

been

logged for any old machinery that could be used for scrap. It took

longer

to acquire supplies of coal and this was of poor quality.

The war created a heavy demand for lumber and a few specialized uses were tried out including cutting sound, straight grained spruce for airplane construction as well as hardwood for propellers. A veneer mill was opened in 1941 to produce birch veneers required for sewing machine cabinets and to avoid the need to purchase veneer from the United States. In 1942 the line was extended a further five miles to Creek à John (or Jean) at mile 43. The contractor was Carneil and the Plymouth locomotive was used for much of the time. Sir Douglas Alexander came in September to inspect the work and to stay at the newly completed Lac Barrière Depot. The supply of manpower became a problem. For example, when Osias Richer, the regular fireman on #2, became sick there was nobody to replace him. In the end it was decided to train another company employee as fireman with Osias travelling along to show him how to fire the locomotive. There was no possibility of recruiting anybody from outside. Also in 1942, a short spur was built from the main line at mile 23.1 to Baie de l'Ours. A run around track was constructed at the end so that logs could be loaded directly from the water to rail cars. These logs were driven (i.e. floated) from as far afield as Lac Gagnon, via the Rivière Petite Nation, across Lac Simon and Lac Barrière. Logs had previously been loaded on the main line at this point before the spur was completed. The construction work continued in 1943. The Plymouth was available for this work as another locomotive had been borrowed from St-Jean to work Thurso yard. This year the end of steel was extended from mile 43 to mile 47 and the short Long Lake Spur was constructed to Camp 15 on the shores of Lac Gagnon. Rails were in very short supply as were men to carry out the work. Damien Lafleur was criticized for employing small boys in the rail gang. Mr. Bourget instructed him either to lay them off when able bodied men became available or to put them on less onerous work such as shovelling ballast. A concerted effort was made on the track laying by some 21 men from all departments of the Company who were willing to go into the bush at the end of June to complete the job.Click here for detailed construction reports. The government began to exercise a significant control over the Company's relations with its employees. The operation was classified as a "designated establishment" and there could be no hiring, firing or quitting without government permission. Notices were posted: AND THE SAKE OF YOUR FAMILY AND FRIENDS HELP BEAT HITLER BY REGULAR ATTENDANCE AND THE BEST WORK YOU CAN DO In the fall of 1943 some German internees were moved into Camp 15 to help with the railway construction and to work in the woods. This was under a contract between the Singer Company and the federal Labour Department. The numbers varied from an initial forty to a high of between fifty and fifty-five. Among them were six or seven captured German armed forces personnel but most had been interned. They did not require a high level of security although this was in the charge of a tough Warden Landriault from the Bordeaux prison in Montréal. The few guards were all Singer employees. The prisoners were paid 20 cents a day and this had to be taken in kind, mostly in the form of cigarettes or chocolate. The work was not too hard and the atmosphere was quite relaxed in spite of the tough warden. Many spoke English or French and developed a good rapport with their captors. One area of friction was the cooking because the German cook prepared food the German way. This was very well for the internees but it didn't sit too well for the Canadians who particularly hated a stew which was continually on the boil, with new items being added to replace stew that was taken out. The warden spoke to the cook and the food became more acceptable. Everyone could then enjoy the bounty of the woods such as the rabbits which were easily trapped and the deer that were silly enough to put their heads through snares set out for the purpose. At times the internees required dental treatment which entailed a visit to the dentist at Buckingham. These treks by the men in blue uniforms with a large red circle on the back, came to be well known throughout the area. It was a long journey by TNVR to Thurso and then on the CPR via Masson to Buckingham. One time, on the way back at Thurso, they plied their guards with alcohol and enjoyed themselves in the town. A few weeks later there were red faces when it was discovered that a group of German internees, incarcerated in the impenetrable bush, had contracted venereal disease. There were two attempts at escape. One individual made a half hearted attempt to walk out and reached Singer (mile 26) before he was caught. Two other men were more determined. When the escape was discovered Damien Lafleur took his hunting rifle and set off in pursuit on a locomotive. He quickly caught up to them but had difficulty in cornering them among a pile of logs. The engine was moved up and down alongside the log pile until the men were exhausted and could then easily be apprehended. The internees were well received by the Thurso people and, in general, enjoyed their stay. Most were reluctant to leave when the time came to depart on Good Friday 1944. The following pictures were taken by Fernand Lafleur of the internees and their camp.

In 1944 the main line was extended from mile 47 to the south end of Lac Ernest, then known as Little Long Lake, at mile 51. This was carried out by the Company itself under the general supervision of Barclay Boyd, who had been site engineer for a number of years. The work crew consisted of about twenty men together with one D4 and two D7 tractors and two teams of horses. There were a number of interruptions. Frost in the ground could not be broken by the tractors as late as May 20. Half of the crew were off fighting forest fires in June while some days were lost in July through rain. Dysentery also caused some problems. Click here for detailed construction reports. |

Post-war Extension

The main line was extended along the

west shore of Lac Ernest for about a

mile in 1946 and the final section from mile 52 to Lac Fascinant, mile

56,

was completed in 1946 or 1947.

A significant change occurred in the TNVR operations in 1946 when both steam locomotives were replaced by diesels. The Company took a progressive approach to its motive power and was one of the first in Canada to convert entirely to diesel operation. A 3.5 mile spur was built south westwards from the main line at mile 49.5 in 1949. It passed Lac de la Cruche and Lac Devlin and ended at the southern end of Lac du Sourd. At Lac Devlin there was a double-ended siding right beside a lumberjack camp. The spur was built in a great hurry to gain access to new timber. There was a fearsome down grade for loaded trains and this may have been one of the reasons for its short life. The Lac du Sourd spur was taken up in 1951 as was the Baie de l'Ours spur. The Long Lake spur was abandoned in 1967. There have been numerous changes to siding lengths together with several route revisions. The last of the revisions was carried out around mile 55 in the early 1970s. A major revision was also started in the late 1970s but was never completed. By the mid 1950s the Singer limits, which had been logged of their softwood before their purchase by Singer, were, once again, ready for softwood logging. This resulted in the incorporation on March 16, 1956 of the Thurso Pulp and Paper Company. A 200 ton per day pulp mill was opened at a cost of $21 million on March 13, 1958. As well as the pulp logs, it also used the tops and branches of logs harvested for veneer and lumber that had previously been waste timber. Mill capacity was subsequently increased to 350 tons per day. On October 14, 1958 the Thurso and Nation Valley Railway suffered a serious derailment. Click here for a detailed newspaper account of the 1958 Train Wreck. The newspaper account suggested that if the train had passed by ten minutes earlier it might have raced the tidal wave to the embankment. Pierre Blais had the most serious injuries and his arm was eventually amputated. Albert Desgagnes later said the train was only travelling at 15 mph when he saw the washout but the short train, with its lighter braking, and a thin layer of ice on the rail made it impossible to stop in time. The newspaper provided a somewhat lurid account of the accident but it did give some idea of the horrors of railway accidents. The Journal gave the impression that the car was packed with holidaying woodsmen out to celebrate Thanksgiving. In fact, the woodsmen were travelling to work. There is a company record of those who were involved in the accident. It indicates that out of a total of 43 employees injured, not 33 as stated in the paper, three were still in hospital and eleven were still at home two weeks after the accident. Seventeen employees lost a week or less of employment while twelve lost between one and two weeks of employment. The total loss of personal possessions amounted to $213.95. Between them these two documents provide a complete account of the wreck. There are some detailed differences between the two records but in matters of technical detail the Company should be relied upon. There was one fatality. The washout, which occurred at mile 49.5, scoured a hole 12 feet below the rail and the plunge spelled the end for the first TNVR diesel #4, which was brought back to Thurso and cut up for scrap. Parts of the locomotive survived in the form of flatcar no. 3 and were still giving service 30 years after the accident that brought the demise of the rest of the locomotive. The passenger car, no. 2, was repaired and saw service for a few more years. |

Road Competition

This accident marked a turning point in

the fortunes of the railway. Up to

that time the railway had been the only means of access to the working

areas

in the woods. The next year a dirt road was constructed and the railway

monopoly

was broken.

In 1959 the Company commenced the manufacture, assembly and finishing of sewing machine cabinets at Thurso. Finishing had previously been carried out at St-Jean, Québec. In 1962 the manufacture of Doweloc, a type of boxcar flooring, was commenced. This was a process in which maple stripwood was tongued and grooved and held together with aluminium spikes. A year later the Company commenced the manufacture, assembly and finishing of household furniture. In the same year the Company discontinued the sawing of logs for other than its own uses which were the production of pulp, sewing machine cabinets, Doweloc and furniture at Thurso. These attempts at diversification were fuelled by the increasing difficulties being faced selling sewing machines overseas. More and more countries were demanding a product with greater local content. The end result was that the Thurso operation was sold in 1964 to the James MacLaren Company. 1970 saw a change in the method of operation of the railway. Three 70 ton General Electric locomotives were acquired second hand from the Canadian National lines in Prince Edward Island. Two were rebuilt and put into service as #11 and #12. The third served as a source of spares to keep the other two, as well as #7, in operation. This allowed the removal from service of the lighter 44 ton locomotives #8 and #9. It had always been thought that the lighter rail at the north end of the line would not stand up to the heavier 70 ton units. This proved not to be the case and the last years of operation were characterized by the GE 70 ton locomotives on all main line runs. At the start of the 1970s there arose the spectre of truck competition. Expenses were cut to the bone but the railway was forced to continue using very old equipment and rails that were, in some cases, over a hundred years old. The needs of the mill were being satisfied by lumber that was cut mostly within 35 miles of Thurso. With the vastly improved paved road access to the area, together with better logging roads in the bush, the line had great difficulty competing. The TNVR was discovered by railfans in the late 1960s and a number of trips were run by the Bytown Railway Society (BRS) which is the group of interested railway enthusiasts located in the Ottawa area. The TNVR continued relatively normally in the early years of the 1980s. There were periodic shut downs but this was as a result of periodic economic difficulties and had been a normal feature of the railway operation. Changes had been made in 1981 to the entire fleet of cars, as well as the method of operation, to allow longer logs to be handled. This was accomplished by equipping the carrying cars with log bunks and by using a number of flat cars, without stakes, to provide spacing between the loads. Things looked to be relatively secure after the purchase in 1981 of a further GE 70 ton #13 in 1984 and allowed overhauls to the other locomotives |

Closure

| The railway closed for Christmas 1985 and stayed closed for the first three weeks of 1986. Only one snowplough was run that winter, on February 12. This was a spectacular trip with car 27 and the BRS caboose. The same month the railway employees were told that the railway would close. Operations remained in daylight hours as there was to be no further track maintenance. The final workings were as follows: |

Saturday 10 May, 1986. Round trip to mile 56 with car 27 and the BRS

van

for the benefit of the TNVR employees and those of the woodland

operation.

Saturday 10 May, 1986. Round trip to mile 56 with car 27 and the BRS

van

for the benefit of the TNVR employees and those of the woodland

operation.  Tuesday 13 May, 1986. Last train of logs was brought down from mile 56.

Tuesday 13 May, 1986. Last train of logs was brought down from mile 56.

Thursday 15 May, 1986. The BRS caboose was used on a service train to

mile

46 for the benefit of senior company employees.

Thursday 15 May, 1986. The BRS caboose was used on a service train to

mile

46 for the benefit of senior company employees.

Friday 16 May, 1986. Round trip to mile 46.

Friday 16 May, 1986. Round trip to mile 46.

Saturday and Sunday 17 and 18 May, 1986. Round trips to mile 56 for the

benefit of MacLaren employees, using car 27 and the BRS van with #12.

These

were a great success and the employees were treated to classic railfan

trips

with a photo stop at mile 20, a run past at Lac de la Ferme and a stop

for

a drink at the spring at mile 56 on the way up. On the return there was

stop

at the bridge at Iroquois siding to admire the falls and an extended

stop

for lunch at the Montpellier Golf Club. On these trips, members of the

Bytown

Railway Society fired up the range in car 27 and served coffee.

Saturday and Sunday 17 and 18 May, 1986. Round trips to mile 56 for the

benefit of MacLaren employees, using car 27 and the BRS van with #12.

These

were a great success and the employees were treated to classic railfan

trips

with a photo stop at mile 20, a run past at Lac de la Ferme and a stop

for

a drink at the spring at mile 56 on the way up. On the return there was

stop

at the bridge at Iroquois siding to admire the falls and an extended

stop

for lunch at the Montpellier Golf Club. On these trips, members of the

Bytown

Railway Society fired up the range in car 27 and served coffee.

Tuesday 20 May, 1986. Last train of logs from mile 46. Thereafter

operations

were cut back to mile 26. The same day the Company sold the steel and

the

ties to Valleyfield Metals.

Tuesday 20 May, 1986. Last train of logs from mile 46. Thereafter

operations

were cut back to mile 26. The same day the Company sold the steel and

the

ties to Valleyfield Metals.

Thursday 22 May, 1986. A special was run for the MacLaren supervisors.

A

service train was used as far as mile 26 and a special run was made

with

car 27 and the BRS van to mile 56.

Thursday 22 May, 1986. A special was run for the MacLaren supervisors.

A

service train was used as far as mile 26 and a special run was made

with

car 27 and the BRS van to mile 56.

Friday 30 May, 1986. A work extra with #12 was ordered for 08:00. It

ran

north with two flatcars and the crane in between to pick up good 85

pound

rail that could be used in the Thurso yard. Car 27 and the BRS van were

on

the rear. The train ran to mile 46 stopping to pick up rails from the

rail

racks. At mile 46, car 27 and the van were left in the siding and the

train

continued on to pick up more steel. The whole consist was brought back

to

Lac de la Ferme where car 27 and the van were left on the main line for

the

weekend. It was a beautiful, peaceful weekend during which time not one

outsider

was seen. A locomotive was sent out from Singer on Monday 2 June to

bring

the cars back to Thurso.

Friday 30 May, 1986. A work extra with #12 was ordered for 08:00. It

ran

north with two flatcars and the crane in between to pick up good 85

pound

rail that could be used in the Thurso yard. Car 27 and the BRS van were

on

the rear. The train ran to mile 46 stopping to pick up rails from the

rail

racks. At mile 46, car 27 and the van were left in the siding and the

train

continued on to pick up more steel. The whole consist was brought back

to

Lac de la Ferme where car 27 and the van were left on the main line for

the

weekend. It was a beautiful, peaceful weekend during which time not one

outsider

was seen. A locomotive was sent out from Singer on Monday 2 June to

bring

the cars back to Thurso.

Operations continued as far as Singer into mid-June, 1986 on a daily

basis

to clear out the log dump there.

Operations continued as far as Singer into mid-June, 1986 on a daily

basis

to clear out the log dump there.

Friday 20 June, 1986. A special move was made to take a gondola to Lac

Fascinant,

mile 56. The gondola would be used by Valleyfield Metals to lift the

line.

Car 27 and the BRS van made the round trip. This was the last run over

the

entire line.

Friday 20 June, 1986. A special move was made to take a gondola to Lac

Fascinant,

mile 56. The gondola would be used by Valleyfield Metals to lift the

line.

Car 27 and the BRS van made the round trip. This was the last run over

the

entire line.

Saturday 21 June, 1986. Round trip to Singer to bring out the final

loads.

Saturday 21 June, 1986. Round trip to Singer to bring out the final

loads.

Friday 27 June, 1986. A clean up trip was made to Duhamel with #12 to

pick

up some track materials.

Friday 27 June, 1986. A clean up trip was made to Duhamel with #12 to

pick

up some track materials.

Friday 26 September, 1986. #12, three flatcars and the rail-mounted

crane

with clamshell attached, went as far as Duhamel to pick up salvageable

materials.

The BRS caboose and car 27 brought up the rear. Two beaver dams had to

be

broken out with the clamshell, in one place the track was flooded to

two

inches above the rail. At Singer they picked up two overturned log cars

in

the loading area. These had been cut into pieces as it was easier to do

this

than to bring them back to Thurso on wheels. The geese were flying

south.

By the time they flew south again the rails would be gone. This was the

final

move over the line apart from two forays in January and February, 1987

as

far as mile 2.

Friday 26 September, 1986. #12, three flatcars and the rail-mounted

crane

with clamshell attached, went as far as Duhamel to pick up salvageable

materials.

The BRS caboose and car 27 brought up the rear. Two beaver dams had to

be

broken out with the clamshell, in one place the track was flooded to

two

inches above the rail. At Singer they picked up two overturned log cars

in

the loading area. These had been cut into pieces as it was easier to do

this

than to bring them back to Thurso on wheels. The geese were flying

south.

By the time they flew south again the rails would be gone. This was the

final

move over the line apart from two forays in January and February, 1987

as

far as mile 2.

| The Thurso and Nation Valley Railway is now just a switching operation around the mill at Thurso. Most of the log cars have been retained while locomotives #10 and #13 have been sold leaving #7, #11 and #12. The rails have been lifted from the main line which has been converted into a one way logging road between Duhamel and Singer. Who knows, one day the price of petroleum products may make it worthwhile, once again, to run a railway into the woods north of Thurso. |