Details of Railway Accidents in the Ottawa Area

1950, March 18 - Canadian Pacific - Ashton, Two dead, two injured

Pictures from Bruce Chapman

|  |

|  |

|  |

| |

|

Extract from an article by

Duncan duFresneBytown

Railway Society,,

Branchline, January 1982, Pages 10-11-12.

But Travie Short is remembered

better for

another story. Ironically train number 83's return from Smiths Falls as

an extra is involved, as is Fourth Class train number 89 another

Ottawa West -

Smiths Falls via Carleton Place job that also handled much of the CIP

production from Gatineau. On the night of March 18, 1950, 83's extra

and 89 were

to meet at Ashton, Ont, The extra had a car to set out at

Ashton

anyway, on the business siding parallel to the passing track. The extra

planned to pull their train into the passing track, cut off head end

cars

to the one they had to set out, pull out through the east end switch

and

then back into the business track. It was a bad night, a heavy March

snow

storm with very high winds was lashing the valley. The extra

pulled

slowly into the passing track, 89 was west of Stittsville and eating

away

the time and distance over to Ashton. The crew of the extra had

correctly

left their headlight on as they were not "in the clear". The story goes

that

the wind was whipping the smoke and exhaust, as well as the snow,

around

the extra's front end. As westbound 89 got the extra's headlight in

sight

the wind caused the smoke, steam and snow to obscure the light, then

clear

up, then obscure it again. In the cab of the onrushing 89 this was

mistaken

for a deliberate "highball" signal indicating (illegally) that the

extra

was "in the clear". The hogger on 89 opened, up his throttle and roared

past the east passing track switch not knowing that just ahead,

obliterated

by the flying snow, was the tail end of the Extra, still foul of the

main

line. Standing on the west switch was a ballast car of rock. The 2624

plowed

into it, rolling over in the process, cars piled up in all directions.

The

little station on the south side of the main was demolished. When all

motion

had ceased, 89's engine crew were dead and her head end brakeinan, Tom

Gilmer,

had saved his life by jumping just before the collision. The dead

fireman

was George Hannam, - the engineer was Travie Short.

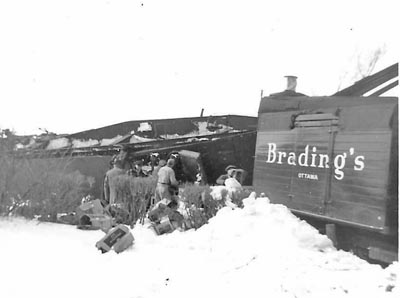

From the Ottawa Journal 19 March 1950 West-Bound Freight Slices Into East-Bound ASHTON, March 18 (Staff) Two Ottawa railway men were killed and two otlhers were injured when a West-bound Canadian Pacific freight sliced into an East-bound freight here at 1.15 a.m. today. Ashton is 20 miles south-west of Ottawa. The dead: Travers A. Short, CPR engineer of 461 Kensington avenue; George H. Hannan. CPR fireman of 23 Adelaide street. Both men were on the west bound train. Local No. 89, running from Ottawa to Smith Falls. The Injured: Thomas C. Gilmer, head-end brakeman, of 217 Riverdale avenue; A. O. Renaud, trainman of 302 St. Andrew street Gilmer, on the west-bound train is in Ottawa Civic Hospital with severe scalds and burns, sustained when live steam from bursting engine pipes enveloped him. Renaud, on the east-bound sustained a fracture of the nose. Ties Up Traffic The wreck tied up traffic on the main Canadian Pacific line between between Ottawa and Toronto, but early morning trains were being re-routed, and wrecking crews hoped to have the tracks cleared within a few hours. The trains met in a blinding, driving snowstorm. Lack of visibllity was believed to have been a contributing factor in the wreck, into which Canadian Pacific authorities already have opened their investigation. How It Happened. , At the moment before impact this was the picture: The East-bound train was pulling into the passing track siding at Ashton. The engine, tender and several cars had pulled over from the main line to the siding, but the tail-end of the freight train still remained on the main track. The West-bound train, running between Ottawa and Smiths Falls, was rolling down the main line and sliced into the last eight cars of the freight pulling on to the siding. How it had happened that the West-bound train piled into the other freight, or why it was the East-bound train hadn't cleared the main line, Canadian Pacific officials would not say. However, there was some reason to believe there had been a misreading of signals between the crews of both trains. Head-end Brakeman Gilmer of the West-bound train was heard to say "He gave us the high sign with his headlight". It .was possible the crew of the West-bound train saw a headlight signal through the driving snow, read it to mean the track was clear, and so continued rolling to cut into the other freight The West-bound threw two East-bound freight cars against the Ashton flag stop station, smashing it and then itself toppled end ever end. The right-of-way was torn up for some 200 yards, littered with splintered ties and twisted steel rails. First rescuers to reach the scene found the body of Engineer Short lying on the ground near his engine, a crumpled figure covered with blood-spotted snow. The body of his fireman, Georgs Hannan. was found locked in the wreckage of the cab, unseeing eyes staring ahead while the oranige glow from the firebox played grotesquely over his features. The scene was one of death and desolation the small flagstop station a crazy mass of splintered boards, rail ends jerked upward as high as 20 feet, the wreckage of box cars which had been crushed like match boxes strewn about the area, and railway ties like toothpicks studding the ground. The eerie bright red and yellow railway flares played over the macabre spectacle as a wrecking crew of 20 men from Ottawa. Stittsville and Carleton Place methodically set about clearing the main line. Engine Flips End Over End. The engine of the West-bound freight had flipped end over end and crashed over on Its left side near the rails, scalding steam pouring from its burst boilers. Near by the tender stood tilted on its nose. CPR offlcisls said the East-bound train had gone to Smiths Falls as local No. 83. and was heading back to Ottawa as an extra freight. The West-bound freight No. 89, left Ottawa at 11.55 p.m. Doctors from Carleton Place and Smiths Falls drove through the storm over drifted roads to reach the wreck to give aid to the injured. Engineer Short and Fireman Hannan were beyond .help. The Department of Highways rushed a snowplow in from Careleton Place minutes after the wreck wss reported to keep the road open for police, ambulances, doctors and rescue workers. Scene of the wreck was some 200 yards from Highway No. 15 linking Carleton Place and Ottawa. From an Ottawa paper (Citizen?) 19 March 1950: Like the Toys of an Angry Giant (with picture) Smashed and tossed

by the trenendous impact of tons of steel, the wreckage of CPR

freight No. 83 lies scattered across the main transcontinental line at

Ashton, 20 miles southwest of Ottawa. The broken cars spew

their

cargo across the snow, the one in the right upper background spreading

hundreds of cases of beer about. Seven cars, the

engine and the tender are spread around in much the same confusion as

would result if a small boy in temper had upset his toy

train.

The early morning collision Saturday of No. 83 with the rear end of

an eastbound freight affected train schedules and connections from

Montreal to Sudbury, while dispatchers rerouted freight and passenger

to by-pass the smash-up in which two crewmen died and two others were

injured. The wreckage was cleared, 250 yards of ripped up

track

replaced and the line opened for traffic again late Saturday.

At

either end of the torn right-of-way, the railway wreck-clearing cranes

can be seen beginning the job of working their way to the centre of the

pile-up. From the Ottawa Citizen 22 March 1950 Thirteen Witnesses Heard In Ashton Train Wreck Deaths Engineer Tells about Signal from Brakeman By Staff reporter CARLETON PLACE Misinterpretation of a brakeman s "that will do" may have been responsible for last Saturday's freight train wreck which cost the lives of an engineer and fireman at Ashton Station. Engineer George Wilson told a coroner's jury here last night that his front end brakeman, William K. Bangs, had given that three-word signal, thereby causing Wilson to halt his freight on a siding before the rear cars were clear of the main line. The inquest, called as a result of the deaths of Engineer Travers A. Short and Fireman George H. Hannan, was adjourned until April 4, after evidence of 13 witnesses had been heard. The adjournment was granted in order to permit brakeman Thomas C. Gilmer, badly scalded in the wreck and still in hospital, to give evidence. Gilmer was riding in the cab of the locomotive of a west-bound freight in which Short and Hannan met death when the engine plowed into the other train. "Bangs was looking out on the fireman's side of the engine," said Wilson. "When he told me 'that will do' I took it for granted the train had cleared the main line and I stopped." In his own evidence later Bangs stated that his signal had meant only that the train had reached the proper point from where a single box car, to be left off at Ashton Station, could be uncoupled and moved into a short siding on the opposite side of the main line. It was the responsibility of the engineer to determine whether or not the train was clear of the main line, he believed. Time Element The time element involved was a major factor over which Lanark County Crown Attorney J. A. B. Dulmage, of Smiths Falls, questioned witnesses at length. The running orders, according to the conductors of the two trains involved, had brought the west-bound freight out of Ottawa to a 10-minute halt at Stittsville. Normally the train would have left that point at 12.40 a.m., but on the night of the wreck it remained there until 12.50, bringing it to Ashton Station at 1.10 a.m. instead of 1 a.m. The east-bound freight arrived at Ashton Station at 12.52 a.m., according to its conductor, Robert G. Macklem of Ottawa. His orders were to drop the single freight car there before the arrival of the west-bound train, provided there was sufficient time. Macklem said the run from Stittsville to Ashton Station required 20 minutes. Knowing that other train was being held at Stittsville until 12.50 a.m., he believed there was a margin of 18 minutes in which to drop the box car from his own freight. Conductor John Gillan, of Arnprior, in charge of the through freight from Ottawa, stated that his train had slowed to between 25 and 30 miles an hour as it approached Ashton. He was out on the rear platform and when he first noticed the other train on the siding. The locomotive's marker lights were burning but the headlight was turned off. "What would the turned off headlight indicate to you?" asked Crown Attorney Dulmage. Headlight Off "It Indicated to me that the other train was completely on the siding and that the main line was clear," Gillan replied. Gillan said that at the speed his train was travelling he could have brought it to a quick stop had he seen any necessity for doing so. "There was an air valve right beside my hand," he said, "but I was confident the other train was well into the siding and the main line clear." Started Into Siding Conductor Macklem said that when his east-bound train stopped at Ashton at 12.52, it halted only long enough for the forward brakeman (Bangs) to open the switch into the siding, then started into the siding. With approximately 12 or more cars still on the main line, the train halted again. When it failed to continue he got out of the van to Investigate. "Could you not have made some sjgnal to the crew up front?" asked the Crown At torney. "No, not then. There was no crew up front to signal to because the engine had uncoupled and moved off by then," Macklem said. The conductor said he went back Into the van to get fusees with which to signal the westbound train in case it should come up while the main line was blocked. He had just stepped back outside with the fusees when the crash occurred. Was His Duty Oscar A. Renaud, rear brake-man on the east-bound train, said it was his duty to close the switch into the siding the moment the freight was clear of the main line, then to "high ball" his "mate up front. " When the train finally halted completely while its rear section was still on the through tracks, Renaud said he was puzzled. "Why did you not signal your crew up front to let them know the line was not clear?" asked Crown Attorney Dulmage. Renaud replied: "We do not signal until the clearance has actually taken place and the switch is closed again. If I had signalled under the circumstances the crew up front would have believed the line to be clear.'' The brakeman said that under normal circumstances the "spotting" of a single car into another siding required anywhere from five to seven minutes, "depending on the speed of the movements." "Then how do you account for the fact that it took about 18 minutes that night?" the Crown wanted to know. No Explanation Renaud shrugged and said he could not account for it. "I was not up front," he said, "and I did not see what was taking place. My job was at the rear and I remained there." George Cloutier, fireman of the train standing in the siding, told the inquiry that he distinctly heard Bangs say to Engineer Wilson: "That will do, George," shortly after the train moved in from the main line. "What did you infer from that expression?" asked Mr. Dulmage. "I believed the train was clear of the main line." Cloutier said the box car to be dropped at Ashton had been spotted on the other siding and the locomotive had just coupled up to the train again when he heard Bangs, who was outside on the engineer's side, shout: "Put on your headlight, George!" "I looked out and No. 89 (the west-bound train) was just shooting past. I saw Wilson reaching up to switch on the light and a few seconds later the crash occurred." On that point. Bangs himself stated that he first noticed the other train approaching when it was approximately one-third of of a mile away. "I ran up under the engineer's window and told Wilson to 'get going'," he said. 'I think the train was moving when we were hit." As to whether there had been sufficient time in which to complete the "spotting" of the box car on the other siding, Bangs stated that in his opinion it was the responsibility of the conductor to make the decision. But actually the head-end crew would be in the best position to determine whether there was time. In that case the responsibility, he thought,would rest with the engineer who was second in command of the train. The town hall here was crowded to capacity for the hearing and a number of railwaymen from Ottawa, Smiths Falls, and Montreal were present. The inquiry was conducted by Coroner Dr. J. A. McEwen, of Carleton Place. In asking for an adjournment Crown Attorney Dulmage told the jury that in view of the importance of the probe he believed it vitally important that they should hear the evidence of Brakeman Gilmer when the latter was recovered sufficiently. In the meantime they would have ample opportunity to carefully consider the evidence already submitted. Ottawa Citizen 28 June 1950 Judgment of Train Crews Blamed for Ashton Crash 2 Ottawa Men Killed in March 18 Accident CARLETON PLACE Bad judgment of the entire crew of an eastbound freight train, a coroner's jury last night ruled, caused a wreck at Ashton Station, March 18 last, which took the lives of two Ottawa railroaders. The accident , occurred, when a westbound freight crashed the rear cars of the eastbound train which had stopped at Ashton Station with ahout 15 vans still on the main line. The stop was made to uncouple one car to be left at Ashton. Engineer Travers Short and Fireman George H. Hannnan, Ottawa, on the westbeund train were instantly killed and front brakeman Thomas C. Gilmer, Ottawa, seriously injured. The inquest had been adjourned from March 21, to allow Gilmer to recover from his injuries. In view of the verdict, Crown Attorney J, A. B. Dulmage of Smiths-. Falls said it would be necessary to consult the Attorney-General's Department in case further action was to be taken. Eastbound Crew The eastbound Ottawa crew composed of Robert Macklem, conductor; George Wilson, engineer; W. K. Bangs, front brake-man, and Oscar Renaud, rear brakeman. Evidence was that the east-bound train left Carleton Place at 12.40 a.m. and the crew knew that the westbound freight had a stop order at Stittsville until 12.50 a.m. The westbound was normally due at Ashton at 1 o'clock, but was not expected until about 1.10 a.m. The eastbound arrived at Ashton at 12.52, started to pull into a siding, and then stopped and uncoupled one car behind the engine, which was left at Ashton, on a third line. Mr. Gilmer sole survivor on the front end of the westbound train testified last night that he was in the engine cab at the time of the collision. "It was a stormy night and snow was falling, when we left Stittsville at 12.52. We were due at Ashton at 1.10 a.m. "Were Watching" "The crew was at liberty to make up 10 minutes and arrive at the usual time of 1 o'clock. At Ashton we were watching for the eastbound freight, which we knew should be in the siding. I first saw the train, when we got inside the switch on the siding where the eastbound was stopped with the headlight off, so we felt the line was clear. "As we came up to the train we got a "highball' (blink of headlights) from the east-bound engine that the line was clear. We were travelling about 20 miles an..hour passing the engine, and started.picklng up speed again, but we could have stopped if we'd known the line wasn't clear. "I yelled to my mates that I didn't see lights on the back of the eastbound freight. Then our brakes were put on and the engineer figured on merely a bunt so we braced ourselves. Then it happened. Had Tested Brakes Gilmer said his engineer had tested his brakes as they approached the eastbound. They had signalled and received the right answer that the line was clear. Crown-Attorney Dulmage asked who decides when there is time enough to set off a car. Mr. Gilmer replied it was up to everybody, but the main responsibilty was the engineer's at the front and the conductor's at the rear. "I was watching for the rear-end marker and failed to see it. We passed the east switch and the engine and there were no markers visible until we passed several cars." Question: "Is it a railway rule that the rear-end crew of a train causing an obstruction must signal with lighted fuses 1,500 feet ahead on a clear night and 3,000 feet if foggy?" Answer: "The conductor is supposed to do it or have the rear brakemen carry this out. Three minutes should be enough time to set out such signals." Previous evidence was that the conductor on the eastbound freight had left his rear van and noticed his train was clear -of the main line. He was unable to signal his engineer as the engine was not in sight and he returned to his van to get a fuse signal, but the accident happened in the meantime. The inquest was presided over by Dr. J. A. McEwen, and the jury was composed of James Murray, foreman, Harrison Lewis John Hawkins, James Reynolds and Alan Hawkins of Beckwith Township. From Stittsville/Richmond Region EMC 22 March 2012 Collision of Freight Trains at Ashton on 18 Mar 1950 Ashton Ontario - March 18 was

unseasonably warm this year, one day in an extended warm period that

has seen most of the snow disappear from the landscape. But March 18

has not always been so lamb-like. Indeed, back in 1950, it was a March

lion, with a blinding snow storm hitting the Stittsville and Goulbourn

area. |

Return to Main Page of Railway Accidents

Updated 12 April 2019