Details of Railway Accidents in the Ottawa Area

1942, December 27 - Almonte, Canadian Pacific, Chalk River subdivision.

|

By Duncan H. du Fresne

As I write this Tid Bit it is

just over 57

years since tragedy struck on the evening of December 27, 1 942, at the

Canadian Pacific Railway station in Almonte, Ontario, when a Canadian

military troop train operated by Canadian Pacific struck the rear of a

local C.P. passenger train. Thirty six people died and 207 were injured, many very seriously, when the regular first class passenger train, No. 550, "The Pembroke Local", hauled by light Pacific No. 2518 and consisting of ten wooden cars was proceeding eastward toward Ottawa from Petawawa. At the time operation on the Chalk River Subdivision was by Timetable and Train Order, there were no automatic block signals. The train was crowded as a result of holiday traffic, the weather, and wartime conditions, and was consistently losing time at each station stop. If that wasn't enough fireman Frank Dixon was having trouble keeping the boiler pressure up on the 2518 due, in part, to a leaking flue in the rear tube sheet. The engineer on train 550 was Joe. Sauve and the conductor was M. O'Connell, assisted by J. Morris with Trainmen J. Tunney and T. Gilmar. The weather certainly wasn't helping, in addition to it being dark, there was a rain and sleet storm to contend with. Following train No. 550 was a 13-car troop train from western Canada, bound for Montreal, via Chalk River, Carleton Place and Smiths Falls on the Chalk River subdivision, and then via the Winchester sub. to its destination. It was designated by C.P. as Passenger Extra 2802 East, (2802 being its engine number, a C.P. Hudson [4-6-4] type locomotive), crewed by engineer Lome Richardson and fireman Sam Thompson. Train 550's engine and train crew were unaware that they were being closely followed by a passenger extra but, even so, at Almonte, under the rules of the day they should have been "protecting" (with fusees) the rear of their train as it was outside "station limits" by 170 feet (as defined by the rule book). At Almonte the local was 40 minutes late, arriving there at 8:32 P.M.

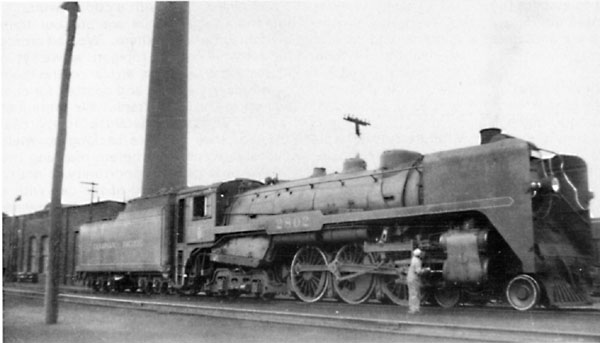

CP 4-6-4

2802 stands on the shop

track at Smiths Falls, Ontario, with those big smoke deflectors. Date

unknown.

The crew of Passenger Extra 2802 East, with conductor John Howard in

charge, were aware that they had been closing up on No. 550 since the

operators at both Renfrew and Arnprior had been ordered by the

dispatcher to hold their train in order to maintain the required 20

minute "block" behind the local. In fact the troop train had arrived at

Renfrew

only five minutes after No. 550 had departed and arrived at Arnprior

only eight behind the preceding train.Approaching Almonte, Passenger Extra 2802 East was proceeding at about 45 MPH at which time speed was reduced to about 25 MPH after a 12 pound brake pipe reduction had been made. The approach to the Almonte station is on a left hand curve approaching from the west, followed by the crossing of the swift flowing Mississippi River. The train order (board) signal at Almonte was briefly observed by Sam Thompson through the mist from the river and the rain and sleet as being "green" (indicating that no train orders were to be picked up). Lome Richardson, on the right side of the 2802 as it rounded the left hand curve could not see the signal or the rear end of train No. 550 because the length of 2802's boiler obscured his view. It wouldn't have mattered much anyway as a train order (board) signal has nothing to do with indicating whether or not the track is clear. In addition to those other restrictions to visibility, 550 was also partially obscured by escaping steam from the tail end car heater line. On the assumption that train 550 had left the station at least 20 minutes before, engineer Richardson released the brake to drift through. As it turned out the train order was green alright, however, this was because the rear end of No. 550 had not yet passed it, the train still being stopped at the station, so the operator had not yet changed it. Neither Richardson nor Thompson saw the local until they were only about 400 feet from it when 2802's headlight reflected off the glass in the rear coach door. Richardson put the brake in emergency, but it was too late. At 8:38 P.M. it happened, engine 2802 struck No. 550, completely telescoping the last car, coach 1028, and partially telescoping coach 1516, the second to last car, stopping midway through it. Both of these cars were reduced to scraps of metal and kindling wood. The troop train consisted of engine 2802, 1 3 heavy steel cars and a caboose, and weighed more than a thousand tons. The elderly wooden coaches offered little resistance to the onslaught or provided safety for the passengers. Fortunately, there was no fire as a result of the collision and there were lots of rescuers. A not-to-heavy jolt was all that was felt by engineer Joe. Sauve and fireman Frank Dixon on the 2518 which shows the frailty of those wooden coaches. Lome Richardson suffered an injured chin, inflicted by flying debris from the wreckage of 550. Sam Thompson came through it without a scratch. Military personnel on the troop train got a minor shaking up, probably as much from the emergency application of the brake as the collision itself. On the local, things were very different. A massive rescue operation began, first by local people in Almonte and the surrounding area, by military personnel from the troop train and Sam Thompson off the 2802. Soon local doctors and nurses arrived and later medical people from Carleton Place, Smiths Falls and Ottawa. A nurse I know was ordered to come to work sometime after midnight at the Ottawa Civic Hospital from her home in Ottawa, as were other nurses and doctors. She didn't know why, and didn't ask, but responded to the call. An Ottawa to Petawawa passenger train was turned into a hospital train at Carleton Place, and the remains of train 550 was similarly made into a hospital train to transport the injured to Ottawa. The town hall and the O'Brien theatre in Almonte were turned into temporary morgues and a place of refuge for the injured. The Smiths Falls auxiliary was called out, however, it wasn't until after 5:00 a.m. the following morning that the line was cleared. Despite the amount of damage to the wooden rolling stock, the rails and ties were, basically, left undamaged. The 2802 had its pilot damaged and the engine truck derailed, really quite minor. Without a doubt it was one of the worst train wrecks in Canadian history. Looking back at that terrible night, from the year 2000, the thought of wooden coaches being used as late as 1942 seems incredible to most outsiders, but was quite well accepted by railwaymen and the rail travelling public alike. Those old cars would outlast the wartime years and still be in service into the very late 1940s, and many into the 1950s. A coroners inquest was established, with a jury of five men, and was held immediately after the tragedy. It was headed up by Dr. Smirle Lawson, the Chief Coroner of Ontario who, after hearing the evidence, was convinced that the C.P.R. should shoulder all of the blame. Obviously the Company disagreed, as did the Board of Transport Commissioners, who blamed many of the employees involved for rules violations. "The inquest concluded that the blame for the wreck must be placed entirely on the Canadian Pacific Railway Company for three reasons: First, they had no operator stationed at Pakenham when in (our) opinion the accident might have been avoided by the 20 minute block system. Second, there was no protective signal at a most dangerous curve, at the entrance to the town (Almonte). Third, the green light showing above the Almonte station gave the engineer of No. 2802 the impression that he might proceed. Had this signal been red, according to the testimony of the engineer and fireman, this train could have been stopped. We place no blame whatever on the crews of the trains No. 550 and No. 2802, but we do feel that an effort could have been made from Smiths Falls to call an operator at Pakenham and Almonte. We recommend that in order to prevent the occurrence of a similar catastrophe and to safeguard the travelling public, especially under wartime conditions: (a) That an operator be placed on steady duty at Pakenham. (b) The immediate installation of an automatic station protective signal west of Almonte. 8 That a standing order be issued for a speed limit not exceeding 25 miles per hour through Almonte and that this order be strictly enforced by the railroad officials. (d) That the block signal device at the station here be changed to give protection to standing trains". At the inquest a great deal of the time was spent discussing the operating rules used by Canadian railways and by which train operation is governed. It is obvious the Chief Coroner didn't understand train operation, or the rules, and became very agitated when they were cited over and over by the various witnesses. In inquest recommendation d) it is obvious he had still not found out what the "block signal device" as he called it, (train order signal), at the station signified. Of course, it only signifies that there are, or there are not, orders for a train. It conveys no meaning whatsoever as to the status of the railway. In retrospect, it could have been a much more meaningful inquest in the opinion of this writer at this late date.

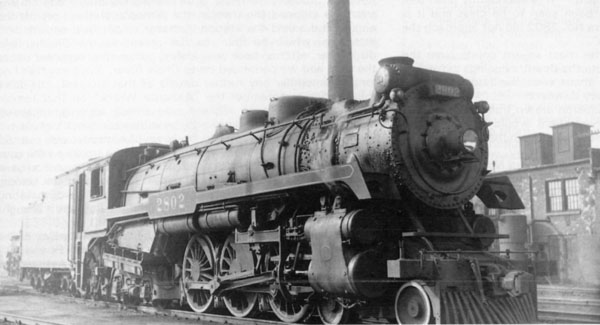

The 2802,

standing on the shop

track at

West Toronto on November 1, 1957. The 2802 likely looked much like this

in

1942, without those "elephant ear" smoke deflectors.

Parties involved at the inquest were, of course, passenger survivors of the wreck, the railway employees involved, the Brotherhoods representing the running trades employees, both minor and major officials of the railway, the Dominion Board of Transport, and others. The Brotherhoods put the blame on the C.P.R., mainly for not keeping the operator on duty at Pakenham, the first train order station west of Almonte. Had that operator been on duty the dispatcher might have had him hold the troop train at that location. The second war years and the holiday season presented a busy time on the railway with extreme demands on the system, as well as the men and equipment, even the Coroner said that current conditions demanded new rules and equipment. Had the troop train been following the rules, to the letter, they should have been able to stop, and had the crew on the local made an effort to protect the rear of their train, there would not likely have been a collision. Fault all round? Probably. Three rules violations were cited in the Board of Transport Commissioners report. First, the crew of No. 550 did not follow rule #36, which states that "a red or yellow fusee, as the case may require, will be used for protection of a train which is not making the speed required by schedule or train order and is liable to be overtaken by a following train". The Board's report also stated that: "The crew of No. 550 had no advice that passenger extra 2802 was following them, but in view of the fact that the train was losing time due to the very heavy traffic incident to the holidays, and having in mind that the rear end of the train was two car lengths out side the west switch at Almonte, good judgment should have dictated to the crew of this train that some protection was necessary, and fusees should have been dropped in accordance with the above mentioned rule". Secondly, rule 91, paragraph 3 states: "Schedule speed must not be exceeded by schedules of trains other than the first section, nor may a train following a train carrying passengers, exceed the schedule speed of such train unless clearance shows arrival at a station ahead". In the Board's report, they elaborated by saying: "This rule was applicable to passenger extra No. 2802 immediately that train was stopped by the train order signal at Renfrew for the twenty minute block on No. 550. It again became applicable when this train was stopped by the train order signal at Arnprior, as has been pointed out [supra] in both instances, namely, between Renfrew and Arnprior, and Arnprior and Almonte. The schedule speed of train No. 550 was exceeded in the first instance between Renfrew and Arnprior by six minutes, and in the second instance between Arnprior and Almonte by five minutes. These two instances of exceeding the schedule speed of train No. 550 form a clear and most serious violation of the said rule, and a major contributing factor to the accident". And, in addition, they also said: "It does not appear that there was any determined effort on the part of the engineer or conductor of passenger extra No. 2802 to actually check their times with the schedule speed of train No. 550, which they knew was ahead of them".

The engine

that powered the

ill-fated local train at Almonte, Ontario, on December 27, 1942, was

CPR's light Pacific No. 2518, shown in Montreal in 1933 with open cab,

little 5,000-gallon tender and single cylinder air compressor. A fine

engine that had a life span of 49 years.

Without a doubt the worst of the three rule violations cited by the Board was rule 93a which states, in part: "The outer main track switches of passing tracks will be considered 'station limits', and main track may be used inside of such limits by keeping clear of first and second class trains. All trains except first and second class trains must, unless otherwise directed, approach and pass through such limits, prepared to stop unless the main track is seen to be clear..." They also said: "It is abundantly plain that the main track ahead had not been seen to be clear and it is equally plain that passenger extra No. 2802 did not approach the 'station limits' prepared to stop". While I have only quoted the most salient points from the Board's report I am going to quote the Board's findings in total so that the reader may compare them with the findings of the Coroner's Inquest, which are very different: "There can be no other conclusion drawn from the facts but that had the rules been observed there would have been no accident. Departure from the rules, resulting in the accident, may be summarized as follows: 30. Failure of the crew of passenger extra No. 2802, and in particular the engineer and conductor thereon, to observe the provisions of paragraph 3 of Rule 91 and Rule 93(a) of the General, Train and Interlocking Rules of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, in that passenger extra No. 2802 exceeded the schedule speed of train No. 550, and that the engineer of passenger extra No. 2802 did not have his train under control and prepared to stop as he approached Almonte Station. It is also felt that the company's official who was riding this train at the time erred inasmuch as he failed to take such necessary action as would ensure compliance with the rules. 31. Neglect of crew of first-class passenger train No. 550 to provide protection by way of red or yellow fusee, as required by Rule 36 of the General, Train and Interlocking Rules of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, to the rear end of No. 550 when it was known that their train was not making the speed required by schedule, and that the rear end of the train while standing at the station at Almonte projected some 170 feet west of station limits. 32. The west approach to Almonte Station is on a curve, and under certain weather conditions a mist arises from the falls near this west approach to the station. The combination of these facts having been disclosed, it appears that the erection of a station protection signal west of Almonte would be an additional safeguard to a train standing at Almonte Station. A direction to this effect will go to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company accordingly". Engineer Richardson was taken out of service. The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers fought long and hard to have him reinstated and were moderately successful in getting him a job as a permanent locomotive fireman on a yard engine in Prescott, Ontario. Sam Thompson went on to finish his career as an engineer working out of Ottawa West. The conductor of passenger extra 2802, John Howard, became victim number 37 when he took his own life (by drowning) before the inquest got underway. He left his son a letter which stated that taking the blame for the disaster was more than he could bear. Nine months short of retirement, John Howard had never been involved in an accident of any kind after 40 years of service. Truly a night, and a nightmare, to remember. One night, about 10 years later, I was the fireman on one of those late night westbound through "western" passenger trains. The engineer I was with, whose name I have forgotten, said he felt sick, probably his heart, after leaving Carleton Place. In any event he stopped the train at the Almonte station, got off the engine and asked the station operator to get help and medical attention, which he did. In the meantime the Smiths Falls dispatcher, after an hour or so delay, got another engineer out to the train and we continued on to Chalk River. I'm sorry that I no longer remember any further details of that incident, but don't think I didn't remember the "Almonte Wreck" on that terrible night 10 years earlier while I was sitting on that engine at Almonte, protected, I might add, by automatic block signals. As an occasional visitor to the town of Almonte, well over 50 years after that fateful night, when I cross the tracks on the road crossing immediately west of the location where the station used to stand, and where the Almonte town hall building still stands, I think about the infamous Almonte wreck and its devastating horror, shattered lives, broken bodies, and the sadness it brought to so many innocent people. The story of the Almonte wreck was first printed in Branchline in December 1988 and was written by Ron Ritchie. Ron, a BRS member and friend, finished up his railroad career as Assistant to the President of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company and now lives in Hudson Heights, Quebec. I have somewhat embellished his original story with details I have learned in the interim, and remembered, and thank Ron for his diligence in keeping so many of the facts of this incident logged as well as so many other "happenings" on the railway. A big tip of the old Tid Bitter's cap to Ron. Tid Bits by Duncan du Fresne, Bytown Railway Society,, Branchline, April 2000, pages 8-10. |

Return to Main Page of Railway Accidents

Updated January 2014