This is my report on a visit to tour the former Canadian

Pacific Great Lakes Steamship, “S.S. Keewatin”, now on permanent display at Port

McNicholl, Ontario. This vessel is part of my personal history as well as part

of the history of passenger steamships on the Great Lakes. The former is

covered in my article for “Branchline” railway magazine, see

http://www.railways.incanada.net/Circle_Articles/Article_Page04.html,

also on file at the Marine Museum. The latter is obviously a much broader

subject, although well entwined with my lifelong interest in railways and

ships.

Background

Before this visit, I was last on board the “Keewatin” in

1959, during one of several family trips from the Lakehead to Port McNicholl on

Georgian Bay. When the “Keewatin” was taken out of service in 1965, I was

saddened at the thought of this fine ship probably facing the scrapyard. After

it and its sistership, the “Assiniboia”, which stayed in freight-only service

until 1967, were gone, the end of Canadian overnight steamer service also

occurred. “Sic transit....”, as they say. It was not long, however, that both

ships appeared to have been reprieved, by having been bought by interested

parties for display and other uses. The “Assiniboia” sailed back down the St. Lawrence River, the first

time since 1907, this time not needing to be cut in half to pass through the Seaway

locks as was the case on the way in from Britain. Her life at a new home in the

US was, however, cut short by a fire shortly thereafter, thus ending her

history.

The “Keewatin” fared much better, having been purchased

by a Mr R. E. Peterson, a US businessman. Mr Peterson set up the retired ship

as a personal museum artefact, at Saugatuck Michigan. Thanks to his loving

care, the “Keewatin” was thus preserved in both mind and body for 45 years

until Mr Peterson could no longer do his best for her.

The current situation

Through the incredible efforts of “Keewatin” enthusiast,

one-time crewmember, and Toronto businessman Eric Conroy, the ship was procured

and moved from Michigan to its former home port of Port McNicholl. The steps

needed to make this move are a story in their own right, many seemingly

impossible. This is not a word in Eric’s vocabulary, however, and his

determination saw the final move take place in the summer of 2012. The ship is

moored alongside its old dock, although about 500m/1500ft further up the bay

than its former commercial docking position. It is the centrepiece of a

development project including luxury waterfront homes, a yacht club and a

property landscaped as in former CPR days. The development seems to be moving

very slowly, and so the “Keewatin” appears somewhat isolated, as shown in photo

no. 1. Let’s hope that this situation improves.

The visit and tour

After a number of email exchanges over the past year, I

finally met Eric in person at a presentation he was making last May before a

service group in Barrie. He said that he enjoyed the 1950s colour slides I had

sent him, showing our family travelling in style on the “Keewatin”, see photo

no. 2.

Photo No. 2 50s Family on the Keewatin

After a short chat, Eric told me to contact him before

any planned visit to tour the ship. I did this and, with my friend Jim from

Barrie, we arrived at dockside on 11 September (2013). Shoreside there are only

visitor toilets (clean...maintained

by “Keewatin” volunteers), everything else is on board the ship, accessible

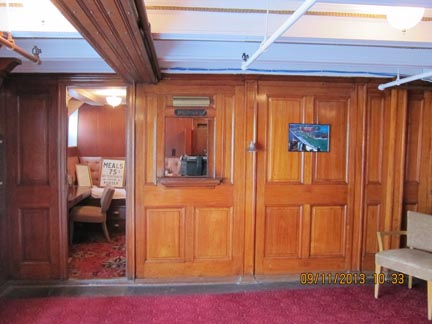

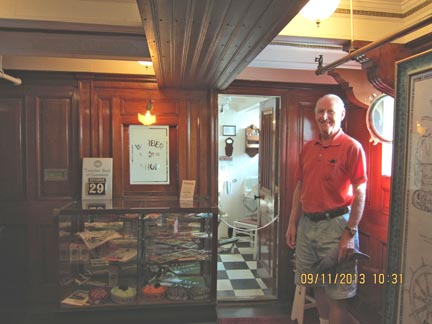

through the gangway doors at dock level. We headed for the “Enter here” gangway

and immediately were at the ticket desk and gift shop. This open space, once

used for c35 automobiles in transit, now has a number of exhibits: photos,

models and artefacts. It is also the site of the Purser’s Office, the “front

desk” back in passenger days. See photo no. 3.

Photo No. 3 Pursers Office

We picked up our senior tour guide, Al Mantel, who, like

all volunteer guides, was sporting a smart-looking CP Steamships shirt,

complete with the CPR red and white checkerboard flag.

Al started with the “technical tour” option (we had

requested both this and the upper decks tours), and headed for a companionway

ladder into the aft cargo hold. I must admit that, while I knew the “Keewatin”

carried freight, I never realised how much...over 2000t.... and where it was

stored. The aft hold is quite large,

when you think that the ship is only 45ft beam. This, and each of the other

holds (aha, now I know why there were so many gangway doors!) was served by a rope

hoist, driven off a fore-and-aft lineshaft on the car deck. Pallets of cargo,

eg: bagged grain, were raised and lowered by these hoists, with the help of

many men. Slow work, but profitable enough for CPR to keep it going.

From the hold, we moved aft past coal bunkers nos. 1 and

2, each holding about 125t of coal. Between the bunkers were the four Scotch

marine boilers, back to back and two across. The two forrard boilers have been

wisely removed, and one of remaining ones sectioned and well-lighted to

demonstrate water and fire passages, see photo no. 4.

Photo No. 4. Boiler Section

In the middle of

the aft coal bunker was a low passageway through to the engineroom...I

recognised it right away!

Now, the engineroom....what can I say: the heart of the

ship! The engineroom is open to escorted visitors. It is packed with machinery,

the centrepiece of which is the 3500hp quadruple-expansion engine which drives

the single propeller shaft. This engine represents the high water mark of

marine steam engine design. The physical size of the engine is mind-boggling.

All the controls are at the base level and easy to see and figure out, see

photo no. 5. The motion of all the reciprocating components can be seen in very

slow motion because an original engine turning device has been motorised for

display purposes. Connecting rods the size of tree trunks convert reciprocating

motion to rotary motion just as they did in real service, see photo no. 6.

Photo No. 5 Engine Control Station |

Photo No. 6 Con rod close up |

The rest of the engineroom contains all the auxiliary

pumps, generators, and other devices necessary to operate a ship of this size.

After plenty of discussion down below, we followed Al

back up to the main deck and started the passenger-level tour. The “Keewatin”

had berths in cabins for 288 passengers and crew space for 84 members. The

former were located on the main and upper decks, in cabins that ranged from

inside with upper and lower berths (no window, washrooms down the passageway)),

to twin beds with ensuite bathroom and porthole or window. For display many

cabins are open to view, with clothing of the era laid out ready to wear, along

with magazines and newspapers of the day. See photo no. 7. This material has

been donated by individuals, and carefully vetted for authenticity. At each

cabin door there is also a small note indicating the cost of this accommodation

at certain years. Most were in the range of $45 - $ 65, some for round trip,

others for singles. Probably not cheap in the day, bearing in mind that the 2 ½

- day voyage was an alternative to the 24 – hour train trip covering the same

distance.

Photo No. 7 Keewatin Suite |

Photo No. 8 Keewatin Flower Lounge |

The public spaces on the “Keewatin” were and still are

very classy. One of the best remembered is the “Flower Lounge”, with its

display of potted live flowers forming a “ceiling” between the main and upper

decks. See photo no. 8. The other lounges at the fore and aft ends of the upper

deck are just as I remembered, right down to the seating. Some additional

furniture and fittings have been donated to fill in the few places where the

originals were missing. These too have been carefully chosen to ensure accuracy

and age.

Photo No. 9 Keewatin Dining Saloon.

The dining saloon on the upper deck is perhaps the most

elegant of all the public spaces, see photo no. 9. Everything in it is

original: china, cutlery, tables. It is set up for dinner and is just

marvelous. The ceiling skylight clerestory has a series of stained-glass panels

which are bright and beautiful in daylight. A Scottish stylish crest adorns one

gable end of the clerestory.

The adjacent bar is woody, dark and polished, with

hand-carved bas-reliefs of the peoples of the British Empire of the day on the

walls.

Now a few words about the crew during operating days.

Their responsibilities were wide-ranging and varied. Hints of crew life are

visible in their quarters, some of which are open to view. One door is marked

“Stewardesses” on a metal plate on the lintel. Inside are three bunks, closets,

and a sink and dressing table. The “Stewardesses” were on board “to attend to

lady passengers’ needs”.

The gallery and bakery employed 17 men, all of Chinese

origin, per Canadian Pacific tradition. The galley produced c 1000 meals a day

in high season. The huge chopping block in the galley is the first and only

one, as fitted in Glasgow.

Other staff included the ship’s officers, with their own

public dining table in the dining saloon, radio operators (the “Keewatin” was one

of the first vessels on the great lakes to be fitted with radar, right after

World War II), deckhands, waiters (nearly all university students),and even a

barber, see barber shop, photo no. 10, and many more in the engineroom and room

steward service, totaling over eighty persons.

Photo No. 10 Keewatin Barbershop

Certain areas on board are not open to visitors at

present, including the open top deck, the wheelhouse, and the radio room. These

spaces are slated for repair and refurbishment and eventually should be open. A

local ham radio club may be occupying the radio room, giving it a realistic

touch.

Before departing the ship, I took one more photo, see no.

11, looking forward from the bow, with a fine view down the harbour toward the

housing development at the mouth of the old CPR port. Much work still has to

done to fill in the intervening space and ensure that the “Keewatin” remains

the focal point of a great project.

Photo No. 11 Keewatin view from bow.

D. H. Page,

Kingston, 24 September 2013.

Footnote:

Port McNicholl is just off Highway 12, about 10km west of Highway 400,

and 10 km east of Midland. It isabout 400km and 4-5 hours drive from

Kingston.