|

It's

later than You Think.

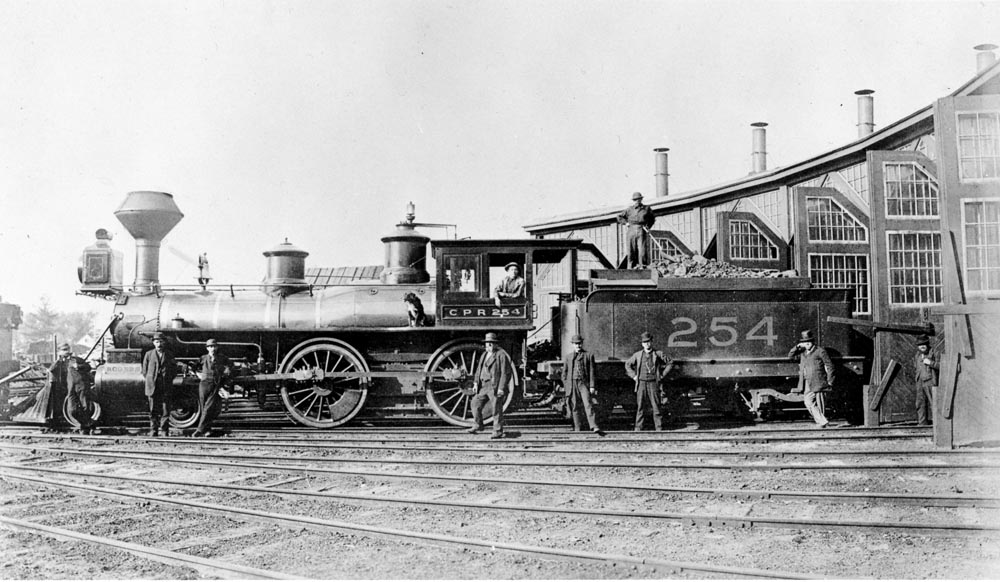

How do you preserve your collection for posterity?   This wonderful photograph illustrates the locomotives used by the Canadian Pacific Railway in Ottawa in the 1880s. This was found in the National Archives and there was a good amount of information penciled on the back. All that is missing is the name of the dog. At first thought this would seem to be a good news story but I found this photo in an uncatalogued box which had no indication of the treasures it contained. This is part of the Merrilees Collection of some 300,000 images which remain largely uncatalogued after some 25 years in the national collection. Researchers have access to this material but it is only catalogued as pictures are ordered. It gets worse. When the Pittaway Company was wound up, it seems that several thousand plate glass negatives were unceremoniously dumped on the ice of the Ottawa River and lost when the ice melted. These negatives were not all railway images but the fact remains that a significant portion of this photographer's work was lost. "Pittaway and Jarvis" was one of Ottawa's early pioneer commercial photographers and this truly valuable collection was lost through ignorance. I have been approached recently by a number of people who have significant railway collections asking what arrangements they should make in their wills to ensure these are not lost. The general approach seems to be "What is the best institution for my executors to send my collection to?" The implication is that all it takes is a friendly call to the institution concerned and then pack up the material and send it off. It is nowhere near as simple as that. While most people are concerned about their slides and photographs it must not be forgotten that other items, such as field notes, books, plans, train orders, timetables (public and employee), papers, tickets, passes, magazines, reports, government documents, newspaper clippings, postcards, models etc., may also be included. If the collection is wide in scope consideration must be given whether it should be disposed as a whole or in parts. For the rest of this article I will use the word "collection" to embrace any or all of these items. Consider the objectives. There may well be a significant advantage to making a donation before one dies. This way the donor receives any financial benefit rather than the estate. With digitization becoming easier and easier it may also be possible to donate the originals yet retain copies to enjoy. Is the collection to be disposed of for financial gain or to ensure that the material is available for future generations to use? From the historian's perspective the worst result is for the collection to be sold off indiscriminately where the material is dispersed into the hands of private collectors. I will assume that the objective is to make the collection available for future generations. I don't intend to get into the argument over what is the best institution to donate material to. There is a large range:  Specialist railway archives

such as the C. Robert Craig Memorial Library in Ottawa and Exporail at

St-Constant, Quebec; Specialist railway archives

such as the C. Robert Craig Memorial Library in Ottawa and Exporail at

St-Constant, Quebec; National Library and

Archives, other national museums; National Library and

Archives, other national museums; Provincial archives or

museums; Provincial archives or

museums; University archives; University archives; Local railway museums; Local railway museums; Local museums and

historical associations. Local museums and

historical associations.Each one has advantages and disadvantages and the decision will depend to some extent upon the scope of the collection. If it is essentially local, a local museum might be good even though the staff may have little railway knowledge, whereas if the collection is more technical in nature a specialist railway archive or museum might be preferable. A factor in your choice of holding facility should include an organization whose views about access and publication are congruent with your objectives. Some organizations charge fees that are almost prohibitive for many authors. With the advent of digital technology and the internet, the choice of location may not be as significant in the future because much material is being made available over the internet. The most important point to bear in mind is that YOU should make all the arrangements well before you die. Bereavement is a very stressful time and things may be done, such as putting collections in the garbage, that will later be regretted. One of the most important persons in settling an estate is the "executor". This person (regardless of whether it is the wife or not) should be made aware of the collection, its contents and the collector's wishes. Unsympathetic executors can be very unhelpful, "Get it out of here or we'll dump it". So you start to look for a suitable location to house your priceless collection. Don't be surprised if the proposed recipient is not overjoyed at your generous proposed donation. Slides and negatives must be housed in an environment with controlled temperature and humidity this is expensive. Boxes and albums of pictures take up space while many early papers will disintegrate without proper conservation. Most museums and archives are underfunded and have very little space available. Therefore your decision on a recipient should also consider the resources (staff /volunteers / facilities) and money that the organization has to preserve and maintain your collection. Essentially it will be your responsibility to persuade your chosen recipient that it is worth their while to hold your material. How do you persuade them? You must first go through the collection and weed out anything that is not first rate quality. Unless there is a very good reason for keeping a substandard image (eg: historical significance or "one of a kind" photograph) discard anything that is blurred or poorly exposed and eliminate duplicates. Digitization can improve some images but nothing beats a sharp, clear image. We all know how important it is to label your photographs with information and dates but it is just as important to catalogue your collection. You need a comprehensive list in electronic, preferably database, format, so that it is quickly searchable. Nobody is going to search one by one through 12,000 slides looking for something in particular - they must be able to get to it quickly. Incidentally, field notes should be retained with the slides or photographs as they explain the sequence in which the images were made. Only you know the details of your collection and it is important to document why you took that picture. At the same time it is essential to prepare a Finding Aid. This is a summary of the collection which sets out the size and scope of the material and description of the various parts. If there is different material in the collection, the interrelationship between the parts should be explained. Set out the important and unique aspects of the collection. The Finding Aid doesn't need to be lengthy but it is important because it is the first document that the researcher will consult. It will help him make the decision whether to delve deeper into the collection.

This may be a lot of work but consider the Aubrey Mattingly collection. This finally finished up in the Canada Science and Technology Museum - in a warehouse out back because nobody knew what it contained. Several years later I went in with another volunteer and offered to catalogue it for the Museum[1].. They were very happy because they had no idea what it contained. It was delivered to a room for us on a pallet - a jumble of boxes and albums. There were just over 8000 prints, slides and negatives, many of them were identified but many were completely blank. It took us two years, one day a week, to produce a catalogue and another couple of years to scan the pictures digitally. Now however, the Museum knows what it has and can quickly retrieve the image for instant use. If you approach an organization with an offer of your collection complete with an accurate record of what it contains and with the ability to find anything quickly, they are much more likely to accept a donation than if the only prospect they have is to see it gathering dust in a warehouse - just taking up space and of little use to anyone. Volunteer cataloguers are few and far between and few organizations have staff with the detailed specific : knowledge to catalogue these collections.  We have all heard stories about the collection that was thrown out and lost for ever. However, many collections remain pretty well useless because they have not been properly described by the owner. I hope these thoughts will spur you to properly document and prepare your own collection to ensure that it remains available to others after you have passed on. DO IT NOW! I would like to thank Bruce Ballantyne, David Knowles, Bill Linley, David Page, Dennis Peters and other members of the Ottawa Railway History Circle (http://www.railways.incanada.net/circle/ ottawahist.html) who have helped me in the preparation of this article. [1] The Mattingly Collection in the Canada Science and Technology Museum by Colin J. Churcher and Bob Moore, Branchline, April, 2004. |

![]()