The Rideau Canal Accident

(For a detailed track plan and additional pictures of the area concerned please see “The Canada Atlantic Railway Elgin Street (Ottawa) Station” Branchline, February 2004, page 7.) Wednesday 12th August 1891 started out as any other normal day for the Canada Atlantic Railway Elgin street depot but before very long it had turned into a nightmare for many C.A.R. employees. Background

Engineer McGaffney and his fireman, Page, booked on early in the morning at the Elgin street roundhouse for the Coteau wayfreight. They picked up their locomotive, No. 33, a relatively new 2-6-0, built by Rhode Island (serial number 2201) and delivered in February 1889, and ran into the yard where conductor Cote and brakeman Gordon were ready to make up their train. They were in a bit of a hurry to get out well ahead of the morning passenger train for Montreal which was due to leave at 08:00. By six o'clock they were pretty much ready to leave, the engine and four cars were on a siding and the rest of the train, twelve cars which had been made up the night before, was waiting on the main line in front of the station. All that was needed was to run out eastwards on to the main line and back on to the rest of the train and they were ready to leave. McGaffney got down from No. 33 and went into the station to get his orders.

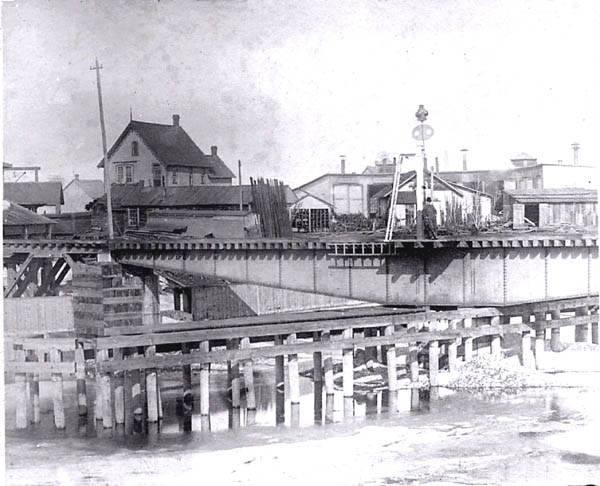

A view of the drawbridge showing the semaphore signal in the centre with possibly the Bridgemaster leaning on the post. Behind the bridge can be seen the Elgin street roundhouse. No. 33 came from the left or west side and dropped into the centre part of the canal. The channel nearest the photographer is the one the tug Minnie Bell was forced to use and which was used by all traffic until the wreck was cleared. This is where the Queensway bridge over the Rideau Canal is located today. (Collection N. Bruce Ballantyne.) The Accident

Cote told Gordon to shunt the engine and four cars on to the main line and finish making up the train while he, presumably, also went to the station to pick up the orders. Gordon signalled to the engine to go ahead and fireman Page, who was alone on the engine, opened the throttle and started to move ahead. He only needed to run about 40 yards on to the main line, but, for some unexplained reason, he continued on further east towards the swingbridge over the Rideau Canal. At this very moment, the tug Minnie Bell was approaching the bridge from the north. It whistled get the bridge open and bridgemaster Wallace opened the bridge. As the bridge turned the semaphore also turned to exhibit a danger signal to railway traffic. Wallace saw 33 approaching and shouted at the top of his voice but it was the frantic whistling of the Minnie Bell which brought Page to his senses. He quickly reversed the engine and applied the brake and it almost stopped but the impetus was too great and 33 went over slowly into the canal going in headfirst but turning over completely striking the water on her back. The coals from the fire dropped in with a hissing sound and created great clouds of steam. The tender followed and finished up on top of the engine. The first car, a boxcar loaded with laths, hung for an instant on the edge and then broke completely in two, as if it had been cut through by a gigantic knife, cascading wood and other debris into the water. Fireman Page stayed with his engine until the last minute and jumped out as it plunged into the canal. Wallace and several others ran to the edge and peered in and were surprised to see Page swimming calmly to the bank. He was helped out suffering from slight shock. Meanwhile, the Minnie Bell was bearing down on to the blockage. With presence of mind, the master went hard a port and managed to steer his vessel through the eastern channel thus avoiding further disaster. The Immediate Aftermath

Strange to say, the delays to trains were not significant. The bridge was not damaged and once the wreckage of the first boxcar was cleared away trains could run as normal. Superintendent McDonald did what railway managers have done since the beginning. He held an inquiry so as to blame someone. He did this later that morning. It was quite clear who was to blame. Fireman Page did not have authority to run the locomotive, having been with the company for only some two years, and so railway management could comfortably point the finger at Page. However, I don’t think it was quite as clear as that. In talking to the press, the superintendent said that Page did not have authority to run the locomotive but he went on to say that, even so, Page did not need to go as far as he did and, in any case, he should have seen that the signal on the bridge was against him. Reading behind the lines, I believe, that what took place that morning was a regular occurrence. The engineer and conductor were in the habit of going to the station to pick up their orders while their subordinates finished making up the train. The Immediate Clean up

The bridge was not damaged and train movements were quickly back to normal once the wreckage of the broken box car had been cleared away. Thus superintendent McDonald’s problems were quickly resolved. However, this was not the case for Mechanical Superintendent Morley Donaldson who was responsible for removing the engine from the canal. He estimated that the work would take a day or a day and a half (i.e. by Friday or Saturday) but, as we shall see, this was wildly inaccurate. The first priority was to remove all the flotsam and jetsam from the canal. This took all day Wednesday and the next. Floating laths had to be retrieved while a large barge was brought up to assist in stripping the tender down to the frame. Superintendent Donaldson went to Montreal to secure two barges to raise the engine. On Saturday small barge was brought in from the city waterworks department. This contained a diving suit, copper helmet, weights and a hand driven pump to supply air. Mr. James Rouleau descended at ten o'clock and walked around the wreck coming to the surface occasionally while an assistant carefully pumped the necessary breath of life from the surface. He found that the engine was intact although it was upside down.

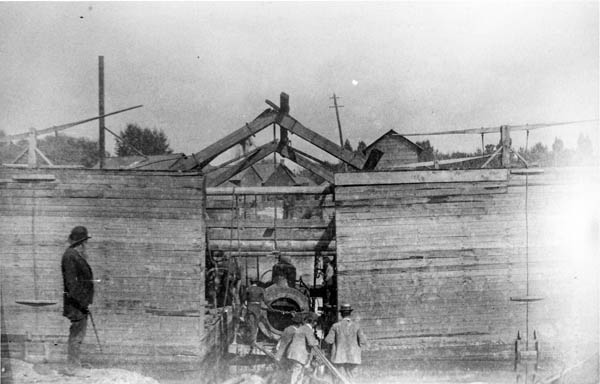

Preparations being made to raise the sunken locomotive taken looking roughly south, September 1891. The siding used to raise the tender and possibly the locomotive as well, is on the other side of the canal bridge running away from the photographer. (James Ballantyne/National Archives of Canada/PA-127265) Raising the Tender

That same day, Saturday the stripped down tender was brought out. A gang of men under the direction of Foreman Holtby gradually worked the tender down the canal from the scene of the accident about 40 yards. At this location there was a siding running parallel to the canal and serving the Silicate Brick Company. Heavy timbers were placed under the tender on which rails were laid sloping up from the water on a ramp to a flatcar which had been placed in the siding. Ropes and chains were then attached and connected, through a double pulley, to an engine on the line at a right angle. The pulley was secured firmly by strong stakes set into the ground. Everyone stood well clear, the word “Go” was given and slowly the coal and water box was raised out of the water and on to the flat car.

The locomotive partly out of the water, September 1891. James Ballantyne/National Archives of Canada/PA-127267) Raising the Engine

Railway wrecking cranes were not generally in use at that time, jacks being used in many cases to retrieve a locomotive. However, raising a submerged 50 ton locomotive presented unusual problems. It was originally thought that barge mounted derricks would be used but this was found to be impracticable. In the end, a combination of submerged caissons or pontoons and jacking was used. The diver managed to turn the locomotive over on 19th August in which position it was easier to raise it. No. 33 was finally raised on Monday 7th September, almost a month after the accident. Pontoons were filled with water and secured to the sunken locomotive. They were then pumped out and, as they emptied, they gradually rose, bringing the locomotive with them. Cross beams were erected under the engine and gradually built up until it was within about five feet from the surface. She was then run on to sunken rails and afterwards hauled on the bank. The account does not explain but presumably the engine was hauled out in a manner similar to the tender.

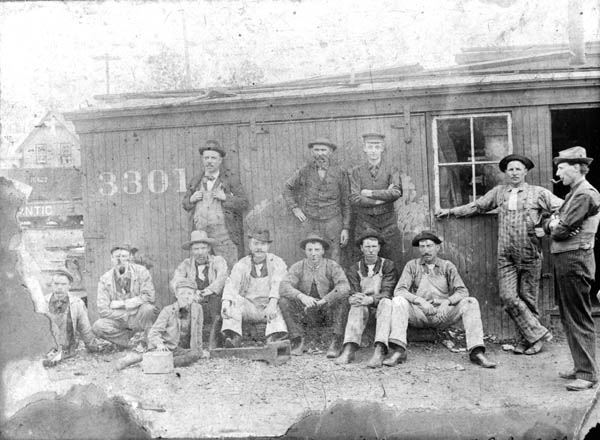

Canada Atlantic Yard Office 1886. It was from here that the moves were planned that would eventually lead to the locomotive going into the Canal. The accident would have formed the subject of much discussion and speculation for some considerable time. The caption reads "Happy Days when the town was wet". From this comment, it seems that rule G which prohibited the use of alcohol did not exist. The Aftermath

No. 33 was taken back to the Elgin street shops and put back into service. It was renumbered C.A.R 683 in 1898. When the Grand Trunk acquired the Canada Atlantic, No. 683 became G.T.R. No. 1350 in January 1905 and was re-numbered G.T.R. 2529 in 1910. It was sold to the Nosbonsing and Nipissing Railway in June 1920. Postscript

There was another incident at the drawbridge on 23rd August 1907 in which a locomotive derailed on the bridge but didn’t go into the canal. After one of these two incidents, the Grand Trunk (or CAR) donated the bell to the nearby Holy Trinity Church. Eventually it was replaced with chimes and the bell now calls the faithful of St. Augustine's Church in Newington to worship. References

The Journal, Ottawa: 8/12/1891; 8/29/1891; 9/9/1891. The Citizen, Ottawa: 8/13/1891; 8/14/1891; 8/17/1891; 8/20/1891; 9/8/1891. Free Press, Ottawa: 8/12/1891; 8/13/1891; 8/14/1891; 8/15/1891; 9/9/1891. Canada Atlantic Railway Research Web Site by Rene Gourley: http://www.proto87.org/ca/ Bytown Railway Society, Branchline, November 2004. |

![]()