|

Head on at Deschenes

October 23, 1924, started like any other morning

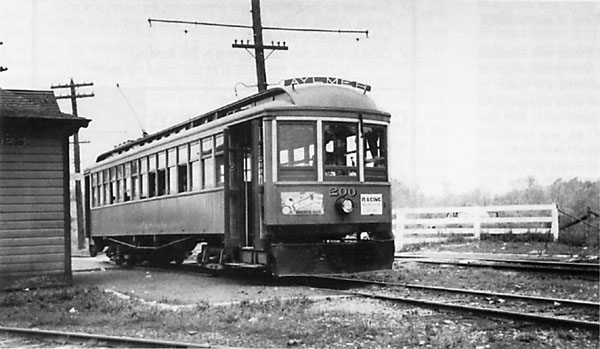

on the Hull Electric Railway. The early morning commuters jammed the cars

coming in from Aylmer, many going straight through to the terminus close to

the Chateau Laurier in Ottawa, while some transferred to the Ottawa Electric

Railway streetcars in Hull, close to where Les Terrasses de la Chaudiere is

today. Inspector Lochnan was on duty at the Deschenes car barns and spoke

to crews coming on duty, telling them that a track crew would be working on

the westbound track between the crossovers at Deschenes and Golf Links and

that all cars would have to use the eastbound track between these two locations.

The line was double track throughout from the Chateau Laurier, across the

Interprovincial Bridge, through Hull and then on to a private right of way

to Aylmer.

Bytown Railway Society,

Branchline, April 2002Things calmed down after the morning rush and conductor Quesnel on car 203 was looking forward to the end of his shift. He left the Chateau Laurier and crossed the Interprovincial Bridge and went through Hull. He was due to be relieved at Aylmer but, with traffic being so light at this time of year, and with an experienced motorman, he judged he could take an early quit and left the car to continue to the end of its run with just the motorman in charge. At Aylmer, conductor H. Bergeron and motorman L. Dupont were waiting to take over and they were quickly away on their first trip to Ottawa. Nothing was said about the track crew working on the westbound line between Deschenes and Golf Links and the car left Aylmer oblivious to the danger that awaited. Meanwhile, conductor McConnell and motorman J. Jacques had left Ottawa on the next departure with car 201. They took the crossover at Golf Links to get on to the eastbound track and motorman Jacques had the controller full open in order to regain lost time. He later admitted that he had been going 28 mph westbound on the eastbound line. Dupont and car 203 was leaving Deschenes and could see 201 approaching at high speed. He thought nothing of it and accelerated away as normal, and it wasn't until he was about eight car lengths away that he realized that they were on the same track. Both motormen applied their air brakes in emergency and the cars were considerably slowed by the time the inevitable collision occurred. The time being 12:15, there were few passengers on board, some six or seven were injured but only one required medical attention. Hull Electric did what all railways would do. They sought to put the blame on someone. In this case motorman Jacques (car 201( was assessed 20 demerit marks for running at too high speed and for failure to have his car under control contrary to instructions. Conductor Quesnel, who claimed that he was obliged to leave his car on account of an attack of the cramps, also bought 20 shares for failure to notify his relief that the westbound track was out of use between Golf Links and Deschenes. Motorman Dupont (car 203) was rather unfairly assessed 5 demerit marks for not keeping a sharp lookout and for being partly responsible for the collision with the other car. In assessing discipline the company used the rule book as a means to assess blame rather than to operate safely. This was thought to resolve the problem. But the problem was, in reality, a management problem and it was good that the matter came to the attention of the Board of Railway Commissioners. Inspector McCaul investigated and he saw things a little differently from the company. The Superintendent of Transportation, Mr. Meech, claimed that, on the morning of the accident, all car crews were given a written instruction issued by Inspector Lochnan, to the effect that westbound main track was cancelled between Deschenes and Golf Links. Mr. Meech also claimed that it was the practice, when instructions of this character had been issued, for the relieving crew to be advised of any orders or instructions in effect. However, Mr. Meech was unable to produce a copy of this instruction and admitted that no signatures were taken from the car crews to whom it was supposedly given. This being the case, Inspector McCaul was at a loss to understand the manner in which this piece of single track was to be operated with any degree of safety, bearing in mind that it was not protected by a regular train order or flagman. The inspector went on to point out: They do not employ train dispatchers, agents, telegraph or telephone operators. No train time sheets are kept of car movements and no time-tables are issued to employees similar to those issued on steam railways, or to electric lines operating mterurban service and following standard practice. In standard practice, the timetable is the authority for movement of regular trains subject to the rules. On most electric lines subject to the jurisdiction of the Board standard practice is followed; operating rules and time-tables issued to employees. No standard practice appears to be followed by the Hull Electric and, in my humble opinion, this accident is the result of failure on the part of the management of the Hull Electric Railway Company to operate their railway in a safe and practical manner.The Chief Operating Officer, Mr. Spencer, followed up with the company by asking it to clear up the method by which one car is kept clear of another on the piece of single track and to advise on the system for taking the signature of each employee for the order issued. Mr. Spencer also wondered whether the system should not include a copy of the order going to every man, and his signature obtained therefor, whether direct from the Inspector or in transferring the control of the car from one man to another.

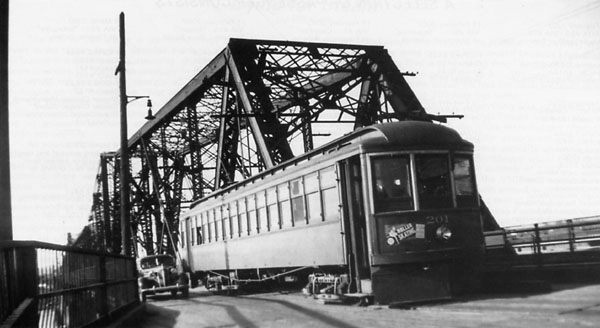

Hull Electric Railway car no. 201, one of those involved in the head on collision, running off the Interprovincial Bridge on a service to the Chateau Laurier at Ottawa. The west side roadway, outside the main spans, was shared by streetcars and vehicular traffic. By this time, it was obvious that the company was scrambling to cover itself. It quickly replied with a proposed draft rule (without admitting that it had currently nothing in place). This is what was proposed: A written order shall be made out by the Inspector stating portion of track to be singled, the period during which single track shall be operated and the crossing points. Copy of this order shall be handed whenever possible to each conductor. The conductor, before proceeding, shall sign the order and also have the order signed by the motorman. Each time a car is turned over to a relieving crew the copy of the order shall be handled to the relieving conductor and the conductor and motorman of the relieving crew shall also sign the order. At the end of the day this copy of the order shall be turned in to the Superintendent by the conductor of the last crew. When it is not possible to hand a copy of the order to the conductor it shall be read to him on the telephone by the Inspector and after the conductor has repeated the order to the inspector a notation shall be made on the order by the Inspector stating the time and the conductor's name. Before proceeding the conductor shall repeat the phone message to the motorman. If the car is then turned over to a relieving crew the motorman and conductor shall repeat the order to the motorman and conductor of the relieving crew.Inspector McCaul quickly pointed out that the Inspector was not the person to issue train orders or to single a portion of double track. Train orders should be issued under the authority of the General Manager or Superintendent of Transportation. He also wondered what would happen if it were not possible to hand the conductor the order. Inspector McCaul concluded that it was not necessary to waste any time on the proposed rules because they do not make for safe operation. There then followed a lot of correspondence in which the company reluctantly agreed to tighten its proposed rule to specify the person who had the authority to issue the order and this is the final version that was satisfactory to both sides. This is the rule that was posted 31 January 1925: A written order will be issued by authority and over the signature of the stating portion of track to be singled, the period which single track shall be operated and the meeting points. A copy of this order shall be handed to each conductor. In emergency cases, the order to the conductor shall be read to him over the telephone. After the conductor has written the order he shall repeat it, and notation shall be made on the order stating the time and the conductor's name. The conductor, before proceeding, shall sign the order, and also have the order signed by the motorman. In case car is turned over to a relieving crew the copy of the order must be handled to the relieving conductor and the conductor and motorman of the relieving crew shall also sign the order. At the end of the day, this copy of the order shall be turned in to the Superintendent by the conductor of the last crew.In his concluding remarks Mr. Spencer felt the new rule should prevent a recurrence. At least the company had learned from the accident and put in place a rule that should have been in place right from the beginning. |