It normally takes several years to train an

engine driver, and it is usually several months, or even years, before

a cleaner is allowed to fire an engine. Thus, when I saw the poster

asking for temporary firemen for the summer vacation I was very

surprised. No previous training was required, and so, being a railway

enthusiast, I jumped at the opportunity to work on the footplate and

see the railways from a different angle.

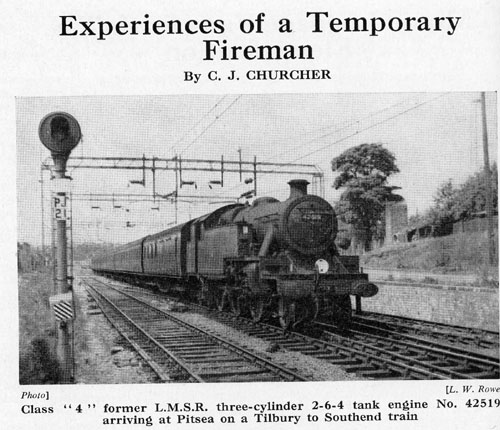

I went for an interview in London. The extra men were required on the London, Tilbury & Southend Line of the Eastern Region, where there was, and still is, an acute shortage of firemen. Having passed a medical examination, I went to Shoeburyness Motive Power Depot. The first few days were spent in the school, where we learned the relevant parts of the rulebook and the fireman's duties on the footplate. The instruction was supplemented by coloured diagrams of engines, and we were thus expected to have a fair knowledge of the locomotive. We were also taken round an engine, and learned the cab layout. The first time 1 climbed onto the footplate I began to wonder what I had let myself in for. There seemed to be a vast, complicated mass of pipes, most of which were very hot. However, it did not take long to become at home on the footplate. At this stage we were taught to couple and uncouple. We practised on a row of condemned coaches which were standing in a siding. The most difficult part of this job is connecting the vacuum brake pipe, which can easily be jammed. Of course, the first time I tried I did jam the pipe, but with practice this is not too difficult. After about a week, we were sent out with a crew to learn how to wield a shovel, and also to learn the road. Most students went as third hand for two weeks, during which time they were upgraded from cleaner to passed cleaner. Thus, after a period of three weeks training, we were considered fit to fire engines. Of course, with so little experience, a great deal would depend on the driver. The locomotives used on the London, Tilbury & Southend Line are two- and three-cylinder 2-6-4 tanks, of both standard and L.M.S.R. design. Most of the drivers preferred the L.M.S.R. variety, particularly the three-cylinder engines. The cab layout of the standard engines is not generally considered good, and the lookout windows are inconveniently placed. One short driver did not like these engines because he could not see out while sitting on his seat. On the other hand, these engines are much easier to prepare and dispose. The rocking grates are popular with the firemen, although they may become jammed by broken pieces of brick arch. The three-cylinder engines, Nos. 42500 to 42536, originally were fitted with exhaust steam injectors, but all these have now been blanked off to work on live steam only. The injectors were sometimes difficult to set. Many were very bad, and it was general practice to look at the overflow pipe every few minutes to check that the injector was still working. Most of the rosters from Shoeburyness are to Fenchurch Street and back. There are, however, several workings to Tilbury, and a few on the Tottenham & Hampstead line from Barking, as far as South Tottenham. The overhead wires for the forthcoming electrification have been erected along the whole of the main line, and over most of the Tilbury line. This means that water can be taken only at Shoeburyness, Fenchurch Street, and Upminster. It is normally possible to work right through to London on a tankful of water, but there is very little to spare, and difficulties may arise if the train is delayed. This may be complicated even further by the fact that water is not available at Upminster when the wires are live. The line is, on the whole, easily graded apart from the climb, in both directions, to Laindon summit, and on the short stretch from Chalkwell to Southend-on-Sea Central, which, in one place, is as steep as 1 in 74. We were mainly kept on shed duties, which consisted of doing the odd jobs around the shed, and firing a train if the regular fireman failed to turn up. This frequently happened, and I spent very few shifts entirely on shed. Before an engine goes off shed there are several jobs for the fireman to do. First, the fire has to be thrown over to raise steam; then the boiler and tanks have to be filled. Tools have to be collected, lamps should be filled, and the firebox and smokebox doors have to be checked. Most of the engines give a very smooth ride. I was rather disappointed because the impression of speed was not so great as I had expected. Some enginemen that I spoke to said that the good riding was due to the four-wheel bogie which is under the cab. However, some of the engines were very rough, and this caused complications, particularly in firing. In the early stages, I hit the firehole ring frequently, but the number of times on a rough engine was much greater. Not only does this spill coal over the floorboards (which one has invariably just swept clean with the hand-brush !) but also jars one's hands. Several drivers said that they would book the engine to have the hole enlarged for me. Once this difficulty was overcome, the actual firing was not too difficult. I was told to fire round the sides and back, and never with a straight shovel (it should always be inclined to one side or another). I had some difficulty in deciding when to put on more coal. We were taught to use the "little and often" technique, which means firing once around the box when the chimney clears of smoke. This shows that the previous fuel has been burnt, and the fire is ready for more. The reason for firing round the sides is that this is where the draught is greatest. All the coal should be broken up but I was frequently told, " If it goes through the hole it's small enough." This can make life much harder because I found that the larger lumps tended to stick in the middle of the firebox, about halfway down. Of course, the "haystack" makes it more difficult to get coal down the front, and I found that the only way was to bounce the shovel off the ring. Some drivers insisted on having the firebox filled right up. This is all right if the engine is a good steamer, but it makes black smoke. It seemed general to use this method on the fastest train of the day, the 9.5 a.m. from Southend Central to Fenchurch Street, calling only at Westcliff (known to the railwaymen as the "Spiv Special"). I travelled third hand several times on this train. The fireman would be shovelling all the way from Shoeburyness Carriage Sidings to Southend. This would usually take us most of the way to London. On the whole, the engines were good steamers, and only steamed poorly if the fire had been badly cleaned by the previous fireman. With the frequent stops on this line it is possible to set the injectors just before the regulator is closed for a station stop. This should keep the boiler pressure down, and stop the valves from lifting, but there were many occasions when the valves did blow, and also times when the pressure could have been higher. This method means that one has to know where the regulator is normally closed : several drivers purposely kept it open when they realised that I was waiting for them to close it. Most of the journeys were quite uneventful, but there were a few moments that did liven up the day, such as the time when the brakes on the train were sticking badly and we nearly went into the buffer stops at Fenchurch Street. Perhaps the most amusing incident was when a horse found its way onto the line. The more we came on the more the horse went on, and eventually we had to stop until it had been caught. Night work is completely different and much more difficult. The steam pressure gauge is far harder to see, and I found it advisable to keep the firedoors open a few inches so that the light reflected off the back of the cab onto the gauge. However, if the doors are open too far, the light reflects onto the lookout windows, making it impossible to see out. The light from the fire is blinding, and I seemed to spend half my time groping around tripping over lumps of coal. I lost all my bearings in the dark, and only had a vague idea where we were; one night I missed West Horndon Station completely. Fog is, perhaps, even worse than the dark. At night, the signals can be seen from some way off, but in fog we had to rely to a great extent upon the automatic warning system. Many of the drivers have their regular engines, and become very attached to them. The system is not rigid and, if an extra engine is required urgently, one of the regular engines may be taken. It does ensure a slightly higher standard of maintenance, which, on the whole, is very low; it was fairly common for an engine to be sent off shed with only one injector working. One driver that I went with was very sad because his regular engine was going to the shops at the end of the week and probably would not come back. He said that it was a very good engine, and that there was very little wrong with it. The next day I had this same engine, which had just been relegated to shunting duty at Southend. This driver grumbled about its condition all the time. I must admit that it was rough; at speed, the boiler, cab, and tanks were vibrating in different directions. However, it is surprising how much better the results can be if the drivers and firemen take a pride in their engines, and also their work. By far the worst part of the fireman's job is disposing of the engine after the run. At Shoeburyness, all engines enter the motive power depot through the mechanical coal hopper. After having taken coal, the engine is put over one of the ash pits. Now the hard work starts. First, the smokebox has to be cleaned. This can be a very unpleasant task if there is a high wind, because the ashes swirl around and, if you have been sweating, stick to your face and hands. Next, the fire has to be cleaned. The fire has to be pushed down under the tube-plate and the clinker removed from the back half of the firebox. This is done with a metal shovel, known as a " short slice." There is not much room to manoeuvre a slice inside the cab and I found that I was constantly dropping hot clinker all over the floorboarding. When the back has been cleaned, the fire has to be brought back under the doors and the front part also cleaned of clinker. For this purpose a longer shovel, called a "long slice," is used. It is even more difficult to use a long slice, which becomes very hot. When the fire has been cleaned, coal is put on, to keep the fire alight until the engine is next used. Finally, the fireman has to clean the ashpan. To do this, he has to go under the engine and rake out the ashes. This also can be unpleasant in a high wind, and is made even worse by the leaks of hot water from the engine. Although it had been quite hard work, I enjoyed my time with British Railways. It was a very interesting job which had fulfilled a childhood ambition. On the whole, the regular staff were very helpful and did much to make things easy for the temporary firemen. Railway Magazine, December 1961. |