The Centenary of the Interprovincial

Bridge

This article appeared in Branchline for February 2001 under the title "Centenary of the Interprovincial Bridge", with subsequent additions. Introduction

The Interprovincial Bridge celebrated its centenary

in 2001. It crosses the Ottawa River from Hull to Nepean Point, near

the National Gallery in Ottawa,. Although it has been a road bridge

since July 1966, the Interprovincial Bridge was conceived and built as a railway

and road bridge. When built, the Interprovincial Bridge, (also known

as the Alexandra Bridge although is does not seem to have been officially

dedicated), had the fourth longest cantilever span in the world (555.5 feet),

after the Forth Bridge at Edinburgh (1710 feet, 1890), the Frisco bridge over

the Mississippi at Memphis (790.5 feet, 1892), and the Liberty Bridge (Szabadsag

Hid) at Budapest (574 feet, 1896). Mr. Guy Dunn, engineer in charge of the

bridge construction, was employed by Horace J. Beemer, who had built the

1879 Prince of Wales Bridge across the Ottawa River.

On 22nd February 1901 the Secretary for the Department of Railways and Canals wrote to Mr. Dunn, Acting Chief Engineer of the Pontiac Pacific Junction (PPJ) and Ottawa and Gatineau (O&G) Railways. By direction, I have to inform you that an inspection has been made of the Interprovincial Bridge across the Ottawa River at Nepean Point, in this City, together with the Approaches to the Bridge in question, with a view to opening the same for Public Traffic. As a result of such inspection, I have to state that there does not appear to be any reason why the said Bridge, &c., should not be opened for such traffic. Your obedient servantThis was written with typical bureaucratic caution which plagued the construction of the structure. While glad to receive the letter, Mr. Dunn could be forgiven for thinking that, at times, the Department had been anything but his obedient servant! On Monday 22nd April 1901 Ottawa and North Western

Railway (ON&W) passenger trains commenced running to Gracefield from the

Canada Atlantic Railway Central station in the Rideau Canal basin. They

were routed over the new bridge instead of from the Canadian Pacific Railway

(CPR) Union Station on Lebreton Flats. The ON&W had changed its

name from Ottawa and Gatineau Railway (O&G) and was building a line from

Hull to Maniwaki, although it had only reached Gracefield at this time.

There were close ties between the Ottawa and Gatineau and the Pontiac Pacific

Junction Railway (PPJ), both of which were built by the contractor Horace

J. Beemer. The PPJ had built a line from Aylmer to Waltham and was building

a connecting line from Aylmer to Hull.

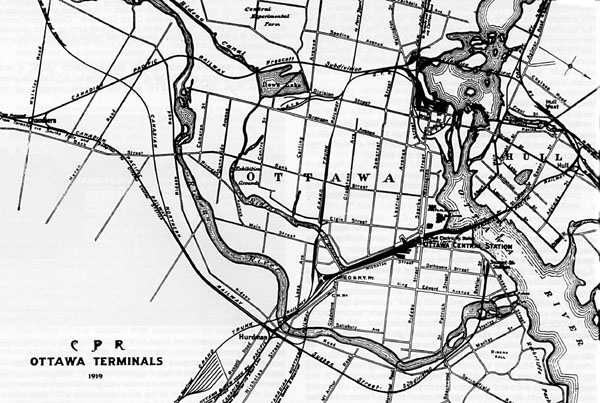

This is a Canadian Pacific map of the Ottawa Terminal area dated 1919, just before CPR passenger trains were rerouted into the Central Station. At this time the Canadian Northern had already become a part of Canadian National, although shown as Canadian Northern on this map. Grand Trunk became part of Canadian National a few years later. The Ottawa Central Station would become Union Station. The Hull Electric station is shown together with its route across the Interprovincial Bridge and the track down to Laurier Street, Hull. The CPR continues at a high level through Hull with the Maniwaki (O&NW) line branching off first to the east (right), the line then curved to the west and was joined by the (QMO&O) line from Lachute before Hull West. The Prince of Wales Bridge is shown at the top (west) of the photo. Background

A number of companies were authorized to build

a railway bridge across the Ottawa River in the Ottawa - Hull area.

Most of these were unable to achieve anything other than a charter and only

two bridges were actually constructed.

In 1871, the Ontario and Quebec Railway obtained a Dominion charter to build a railway from Toronto to Ottawa, via Peterborough, Madoc and Carleton Place and to erect a bridge across the Ottawa River to connect with railways in Quebec. This company should not be confused with a later charter of the same name which was eventually used by the Canadian Pacific Railway. This charter came to naught. In 1879 the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway (QMO&O) was authorized to construct a bridge from Hull to Ottawa. This bridge, the Prince of Wales Bridge, was opened on 3rd December 1880. Compared to the Interprovincial Bridge, it was easy to construct as the Ottawa River is extremely shallow at this location. The Prince of Wales Bridge is now the only rail bridge across the Ottawa River in this area. In 1882 the Ottawa, Waddington and New York Railway and Bridge Company was incorporated to build from Ottawa, via Metcalfe, to Morrisburg, with power to cross the St. Lawrence Canal and River and the Ottawa River. On 29th November 1884 the company submitted a beautifully drawn plan for a combined road and railway bridge to cross the Ottawa River from immediately opposite the Sussex Street Depot of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Railway. This seven truss span bridge would have been east of the present MacDonald Cartier road bridge and west of the Rideau Falls. The company failed because it could not produce a plan for crossing the St. Lawrence River at Morrisburg which would not constitute a hazard to navigation. In early 1880, Messrs. J.R. Booth, F. Clemow, Charles Magee, P.H. Chabot and F. McDougall petitioned for an Act of Parliament incorporating the Interprovincial Bridge Company "to construct and maintain a bridge across the Ottawa River from some point in the City of Ottawa between Metcalfe Square and the ferry landing at the foot of St. Patrick Street (i.e. just below Nepean Point) to some point in Hull for railway carriage, foot and passenger traffic." The Ottawa Interprovincial Bridge Company was incorporated in 1890 (Canada 1890, chapter 92) and it was this company which eventually built the Interprovincial Bridge. The lumber baron, J.R. Booth was prominent in the early days of the company. In 1882, he opened the Canada Atlantic Railway into Ottawa from Coteau and was already thinking of expansion across the Ottawa River and into Quebec. However, the bridge, when built, would fall into the opposing Canadian Pacific camp which was very much at odds with Mr. Booth. There were a number of other schemes to build a railway bridge in this area. The Hull Electric Railway tried three times between 1896 and 1898 to obtain authority to build its own bridge into Ottawa. This bridge, to be constructed under the name of the Ontario and Québec Bridge Company would have extended from Hull to Kent Street or Bank Street. It was opposed by the Ottawa Electric Railway and the interests building the Interprovincial Bridge and the Hull Company was eventually forced to use the latter bridge. Interest in electric railways spawned a number of proposals, two of which resulted in dominion charters.. In 1895 the Deschenes Bridge Company obtained a Dominion charter to build a bridge for railway and other traffic over the Ottawa River from Britannia to the Québec side of the Ottawa River at or above the Deschenes Rapids. In the same year the Ottawa, Aylmer Railway and bridge Company also obtained authority to build an electric railway from Ottawa to the Deschenes Rapids or Remous Rapids, and from there across the Ottawa River to a point in Hull township and to Aylmer. No work was carried out on either of these two projects. Promotion and subsidies

As is the case today, governments were seen as a good source of revenue. In May 1894 the Ottawa Trades and Labour Council added their voice to the appeal in support of the bridge promoters. The council pointed out that the bridge "would be of incalculable benefit to the workingmen, its construction will prove a boon, providing an immense amount of labour during construction, after construction will provide a means of access to work".It was at this time that Horace J. Beemer came upon the scene. He was a Montreal based contractor, who had built the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway and the Quebec and Lake St. John Railway and who was in the process of gathering up the PPJ, O&G and Ottawa Interprovincial Bridge Companies to establish a system of railways in this part of Quebec. He pointed out that it would be impossible for the Interprovincial Bridge Co. (the word "Ottawa" seems to have been dropped in common usage) to undertake the work, estimated at $765,000, without substantial aid from Parliament. Mr. Beemer sweetened the pot by stating that the highway would be free forever to the public and it would be open to the traffic of all railways. The City of Ottawa voted a subsidy of $150,000. Ontario voted $50,000 subject to Quebec granting the same and the Federal government not less than double the amount. Quebec did not come up with any money, hardly surprising when it had financed the construction of the Prince of Wales Bridge, but Ontario eventually made its contribution. The Federal government was not convinced that Mr. Beemer had the resources to construct the bridge and while the location was authorized in 1897 [1] and the structure was authorized in 1898[2], it was not until 1899 [3] that a subsidy was approved. This was for 15% of the cost, not exceeding $112,500. Construction

The original plan had a wagon road on top placed directly over the steam rails. This was changed to a structure giving a wagon road and electric car track, also a foot passenger way, on each side of the steam railway track. The earlier design was impracticable on account of the steep gradients that would have been required for the wagon road on the Hull side as well as gradients on the bridge itself. Mr. Beemer came to the conclusion that, with the growth of Ottawa and the entrance of other railways, he needed three tracks between the bridge and Central station, one for the steam railway and two for the streetcars. In order to accommodate the three rail tracks and minimize the land taken for the ledge to be cut below Majors Hill Park, a siding, originally planned at this location, was left out of the final plan. There was much concern in the community as to location and the effect the bridge would have. The Ottawa River Navigation Company pointed out "the bridge will interfere with the free navigation by ordinary river craft if it is placed at a less height than 45 or 50 feet from high water. Our steamer EMPRESS could not pass under a bridge which was lower than 43 feet."On 21 February 1898 the Montreal, Ottawa and Georgian Bay Canal Company wrote that "the bridge the Pontiac Pacific Junction Railway is proposing to build at Nepean Point is not a swing bridge neither is it intended to be placed at sufficiently high level to allow large vessels or Gun boats to pass under as contemplated by the Georgian Bay Canal Company. Government should not permit the bridge to be built in its proposed form or at its proposed height as the interests of commerce and the defence of the country will be thereby injured."These requests were ignored and in March 1898 [4] it was decided that there should be a clear headway 32 feet between extreme high water of 1876 and the lowest member of the superstructure.  This picture has just come to light in 2021. This

shows shows the half-built 247-foot south span of the Alexandra Bridge

just after it had been floated across the river and placed on piers 1

and 2. The five steel scows supporting the wooden falsework under the span are still there. Much of Nepean point was cut away to create the bridge approach. It used to be a treed slope down to the river. The two short conventional spans of 140 feet and 247 feet on the Hull side had been built in January 1900. Unfortunately LAC has this image reversed (A-102708), so it has been reversed.

City of Ottawa Archives photo CA-19928. On 10th September 1898 the Company wrote to Collingwood Schreiber: The caisson for pier No. 2, the deepest water pier of the Interprovincial Bridge, is now being constructed and will shortly be placed in position for receiving the concrete. The saw dust has been, to a great extent removed, and the balance will be taken out from the inside of the caisson.However, four days earlier, on 6th September 1898, the New York and Ottawa Railway bridge over the south channel of the St. Lawrence River at Cornwall collapsed while under construction with the loss of 15 lives. The method of pouring concrete through the water was similar to that proposed for the Interprovincial Bridge and the Department eventually stopped all further work until the method of pouring the concrete was proven sound [7]. On 12th November 1898 the Company wrote again to Collingwood Schreiber I am informed that you object to the construction of No. 2 pier being carried out in a manner similar to the system adopted in piers nos. 3, 4 and 5. I consider this a superior method inasmuch as all risk to damage of concrete by pumping is eliminated….. The concrete we purpose (sic) using in pier no. 2 will be composed of 1 of cement, 1 of sand and 4 of broken stone. The cement is to be of highest grade of either English, German or PortlandPier no. 2 consisted of a caisson some 68 feet in height filled with concrete with a masonry top some 31 high. The caisson was sunk through sawdust 15 feet to the bed rock which was found smooth and sloping. Holes were bored with a diamond drill and the bottom levelled and roughed by blasting. The bottom was then inspected by a diver and found satisfactory. The concrete was deposited by a 1½ yard bucket with double flap doors on the bottom, which opened downward and allowed the concrete to remain on the bottom when the bucket was hoisted. Over 100 bucketsful were deposited in water 70 ft. deep in one day of 10 hours. Twenty four feet of concrete was deposited through the water in the caisson, when, on 17th October 1898, the work was stopped on the instructions of Collingwood Schreiber. Work was suspended from 17th October until March the following year and then permitted to proceed provided borings through the concrete proved it of good character. When the work was resumed the mixing machine was set up on shore and the concrete mixed with heated sand and water and taken in sleighs across the ice to the crib. The contractors established a 10 h.p. boiler on the deck of the scow and discharged live steam from it into the water to warm the interior of the crib which was filled with water circulating freely from the river. To test the effectiveness of the method of depositing the concrete, a bucket full of it was lowered to the bottom of the crib, then drawn up to the surface, again lowered a little, dumped in a submerged box and allowed to set there. When it was examined it was strong and sound, with no evidence of washing or deterioration by the movement through the water. The filling of the caisson of pier no. 2 was completed by concrete of the proportions of one cement, one of sand and three and one half of broken stone, which was exceptionally rich. The concrete was allowed to set from 1st April to 19th August 1899. Diamond drilling was then in its infancy and some difficulties were experienced in obtaining the core samples. A 3 in. bit was drilled down to within a few feet of the bottom, the hole cased and a 2 in. hole drilled the remainder of the distance. A core was recovered from the whole depth of the hole, which was in every way satisfactory, showing that the concrete was well set though still green. One diamond-drill hole was bored nearly to the bottom of the concrete and a second one was bored entirely through it and into the bed rock. The core was recovered in short pieces less than 12 ins. long and did not, of course, measure up equivalent to the length of the hole, but did give data of the condition of the mass at all depths. About 4 months were required for the drilling of both holes. The other five piers presented very little difficulty, being constructed in less deep water although excavation through up to twenty feet of sawdust was required. Piers 4 and 5 were built through ice 30 ins. thick, in shallow water, on rock bottom so level that the cribs were sunk with their lower course of timbers hewed to fit the smooth surface. Eganville stone was used for piers Nos. 1, 2 and 3, Rockland stone for piers Nos. 4 and 5 while Terrebonne stone was used for pier No. 6.

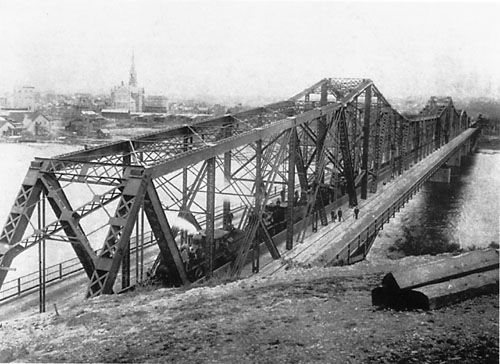

Ottawa Transportation Co. tugs Florence and Dolphin towing into place part of the cantilever span of the Interprovincial Bridge on 21 April 1900. The span is being floated into position on four of five steel scows built by Dominion Bridge at Lachine for this project. They were100ft long 26ft wide and 8ft deep, sheeted with 4 inch pine The unfinished bridge is on the left showing the cantilevering of the two roadway sections outside the main railway section. Compared to the piers, construction of the superstructure was relatively uncomplicated, one hesitates to use the word "easy" in such a project. A contract was signed with Dominion Bridge on 21 September 1899 for this work and five floating scows were moved from Lachine to Ottawa with the erecting gear to carry out the work. The steel was brought to the north end of the bridge in Hull by rail. Accounts of this vary, it may have been delivered by the Hull Electric Railway while other reports suggest a temporary siding was laid in from the CPR north shore line. The south approach from the end of the bridge to Central station, Ottawa, was over half a mile in length. It was, for the most part, cut out of solid rock, and had an outside retaining wall for the entire length built of heavy masonry, in some places being 50 ft. high. In this length were included two heavy steel structures for three tracks of railway, one bridge carrying the railway over the waggon road which lead from the bridge to the city and the other being a steel trestle 300 ft. long, and in places upwards of 60 ft. high, carrying the railway over the government road to the ferry boat landing. No alterations were required to the Dufferin Bridge but it was necessary to cut through the abutment of Sapper's Bridge which was built in 1837 by Colonel By. The total thickness of the abutment was 24 ft., the outside walls in some places being only 2 ft. thick. The filling between the walls was composed of earth and some small broken stone. The stone was in fairly good condition with the exception of about 2 ins. on the outside, at which some 60 year's of Ottawa weather had had a chance to work. On 2nd May 1900 trouble loomed in another direction. A buggy owned by T.G. Brigham Coals, was driving down the Government Road to the ferry. It was smashed by a large rock which rolled down the embankment. The horse was thrown in the river and two men were cut and wounded. The ferry was the only navigation between Hull and Ottawa at that time because the great fire of Ottawa-Hull of 26th April had damaged the road bridge at the Chaudiere. T.G. Brigham Coals was taking items free of charge sent by the Relief Committee to the ferry. Following pressure from the Department, the railway placed additional watchmen when blasting was imminent. However, Mr. Brigham was not easily placated, claiming that he had to send coal for the ferries all the way round by wagon to Hull because the Government Road was almost impassable. The Department sent an Inspector to look at the problem and concluded that Mr. Brigham had no case. Delays in the completion of pier No. 2 gave the railway a good excuse to pressure the government to increase the amount of subsidy which was far less than the $250,000 originally requested. The delay of five months, and the exhaustive tests of the pier, while of great value to the Department, was a great hardship to the Company. It pointed out that the tests turned out to be totally unnecessary. A delay in acquiring the right of way along Majors Hill Park prevented the closing of the contract with Dominion Bridge for the steel superstructure until a large increase in the price of material had occurred. Together with increases in labour costs the company claimed the bureaucratic delays amounted to $160,000. In November 1900 [8] an additional $100,000 was approved. The subsidy contract gave until 1st August 1900 to complete the work. This date could not be met and the time for completion was extended until 1st November 1900 [9]. The plans for the approach on the Hull side of the bridge were not finalized until October 1900. It had been the original intention to construct an earth fill but a temporary round timber trestle was finally chosen. The 1st November 1900 deadline was extended until 1st August 1901 [10]. The last pin was put into the active span on 7th October 1900 and Dominion Bridge completed its part on 26th November. The first locomotive went over the bridge on 12th December 1900 (see picture No. 3). Work continued through the winter of 1900-1901 and on 13th February 1901 Mr. Dunn wrote Collingwood Schreiber that the work would be completed that evening and requested an inspection. This took place on 16th February 1901. Mr. E.V. Johnson, the Inspecting Engineer, made the following report (extracts) to Collingwood Schreiber I was accompanied by Mr. Guy Dunn, Chief Engineer, Mr. McCallum, Ontario, Govt Engineer, Mr. R.C. Douglas, Bridge Engineer (Department of Railways and Canals) and Mr. Campbell, Superintendent of Roads for Ontario. The south approach starts from a junction with the Canada Atlantic Ry at the Central Station, immediately south of the Sappers Bridge - thence through, or under the Sappers and Dufferin Bridges. The old masonry of the Sappers Bridge has been removed for a width of 35 feet, the space being spanned by 10 24in I beams to carry the bridge floor, which is composed of concrete and sepia(?) block. This work is done in accord with the approach plan except that an extra I beam has been placed, making 10 instead of 9 as shown. Dufferin bridge has not been disturbed. There is a clear headway under Sappers bridge over the rails, of 22 feet, and under Dufferin bridge of 21ft 6ins. The line continues to St. Patrick Street, a distance of about 1700 ft. on a rock cut embankment of sufficient width for three tracks. This bank is protected by a very substantial, well built, dry masonry retaining wall. At the foot of St. Patrick Street, and over the Government Road leading to the River and Canal there is a steel trestle for three tracks, 270 ft in length, composed of 9 spans of 30 ft each, resting on concrete pedestals, with stone caps. This structure is well built, and completed in conformity with the approved plans. Beyond this structure the rock bank continues for about 200 feet where there is an opening access for the new highway from the Main Bridge - over this road the three tracks cross on a half through plate girder bridge. Four 48in girders on first class masonry abutments, allowing a clear height of 14'-6" over the highway. The ties on this bridge, as well as on the preceding trestle are 8"x11" 4" apart. There are two guard rails on either side of each track - outer 8"x9" and inner 5"x8" with angle irons on inner side. The rock bank continues from this bridge to the Main bridge over the Ottawa River. Between the Main bridge and the foot of St. Patrick Street two roads have been constructed for highway traffic, one leading to the bridge, for all traffic to Hull, skirts the foot of the cliff and continues over the east roadway of the bridge - the other for traffic from Hull is on the west side of the railway, passing under the track at the bridge last described, and connecting with the east roadway near St. Patrick Street. These are well built roads, on either solid rock or rock bank finished with broken stones, properly rounded off and drained - a sidewalk of plank protected by a neat and substantial railing of iron pipes and cedar posts skirts each roadway to the bridge. The embankment forming the south approach, is fully ballasted with broken stone, laid with 75 lb. rails with angle plate joints, well lined and surfaced. The ties are 2640 per mile. Ottawa River Bridge consists of 60ft of steel trestle on first class masonry abutment and pier - a cantilever bridge composed of 2 anchor arms of 247 ft each, 2 cantilever arms and suspension span forming the main span of the bridge 555ft-9ins, centre to centre of piers - one through truss of 247ft - and one of 140 ft span. The substructure consists of six (6) piers. These are formed of concrete on solid rock foundation, to a height of 2 feet below the lowest water mark - then first class cement masonry. The total width of the bridge floor is 60 ft, comprising 12 ft space for single railway track, a foot walk on either side of 4'-2", inside of the truss members - a space outside the truss members of 16ft for roadway and electric railway tracks, on each side of bridge - the whole protected by a substantial iron railing. A board fence has been placed on each side of the railway track, 3 ft high. The floor for the railway track comprises ties 8"x11" 4" apart, the latter having angle iron protection. The North Approach comprises the following structures beginning at the most northerly pier (No.6) - 390 ft steel trestle on concrete pedestals with stone caps (13 spans of 30') All the works connected with the bridge and approaches are built according to approved plans and are well finished. The electric tracks are laid on the bridge.

View from Nepean Point looking towards Hull and showing the load testing of the bridge with four locomotives. This was the first run over the bridge on 12 December 1900. Four locomotives of the Ottawa, Northern & Western Railway were used with #3, (later CPR #229) in the lead. The northbound roadway can be seen with streetcar tracks in place although the wires have not been erected. The pedestrian walkway, with its low barrier is inside the main structure of the bridge. After a thorough examination and full consideration of the matter, I have reached the conclusion that trains crossing the bridge, as at present fenced, would be less liable to frighten horses, or other animals on the bridge, than if the high fences were erected on each side of the track. Those who are accustomed to the handling of horses are aware that if the animal is able to see the object causing the noise and vibration it is less likely to be frightened that in cases where the object is hidden from view; as City Engineer Galt signed his approval upon the plans of the bridge as constructed, he, no doubt, must have shared my view of the case. I therefore decide that the proposed fifteen foot fence on each side of the track is unnecessary; but I am strongly of opinion that there should be a rule in force, which should be strictly observed, that no engine driver should be permitted to blow off steam, to whistle, or to open the cylinder cocks, while his train is upon or crossing the bridge.On 5th March 1901 the bridge was opened to public road traffic after the City Engineer sent to City Council a certificate approving the work. [11] Subsequent events

A satisfactory test of the bridge was carried out 19 April 1901, by loading it with four locomotives and ten cars loaded with steel and stone, giving a total weight of between 450 and 500 tons, the deflection on the cantilever span being about 2 inches both in dead and running load.[12] Although the bridge was ready for trains in February 1901, the 1.87 mile connection to the Gatineau Valley line was not completed until the following April. The inspection took place on 15th April 1901 and another "obedient servant" letter was sent to the railway the following day [13]. The first scheduled train across the bridge arrived on Monday 22nd April 1901.

This is an early picture of an Ottawa, Northern & Western train running towards Central Station along the ledge under Majors Hill Park. The two outer street car tracks are not yet being used because the wires have yet to be strung up and some additional lining and levelling still needs to be done so this will place the date as April 1901. "The Interprovincial bridge was opened for railway traffic yesterday morning when the first train of the Ottawa, Northern & Western railway, formerly the Ottawa & Gatineau, crossed to the Central depot. The handsome engineering structure was decorated with flags, as was also the locomotive and cars of the train, which was the regular morning express from up the Gatineau (i.e Gracefield).Engineer McFall was killed when his train ran into a washout two miles from North Wakefield on 14th April 1911. He stuck to his post and only the engine toppled into the hole. Forty passengers were saved as the remainder of the train remained upright. Engineer McFall, who was badly scalded by steam, died on April 16 and was subsequently awarded the Edward Medal for his heroic actions. The Hull station mentioned above must have been a temporary one because the ON&W did not start building a permanent one until that summer. Known as Hull Beemer to distinguish it from the CPR Hull station, it appears to have been finished late in the year. "It is in the Elizabethan style of architecture, and is built of stone and pressed brick to the height of the first story, above this in half timbered work. The dimensions of the building are 50 x 24 ft. It contains a large general waiting room with lavatories connected, a ladies waiting room about 16 ft. square with lavatories etc. and dispatchers' office opening into the general waiting room, all on the ground floor. In the basement is a hot water heating apparatus. The first floor is arranged for the stationmaster's house, with six good sized rooms, including a large living room, kitchen and bathroom. The baggage rooms are 136 x 20 ft., and in close proximity to the station and practically under the same roof, which is extended from the station to cover them."[15]Euphoria on the new service was short lived, however, as the Ottawa, Northern & Western quickly increased its commuter fares to cover the costs of the bridge. Many of the commuters were also Ottawa taxpayers who had funded the city bonus granted to the company. [16] The Hull Electric Railway was unable to obtain authority to build its own bridge into Ottawa and was forced to negotiate with the ON&W. The first streetcars did not start to run over the bridge into Ottawa until 25th July 1901. The Ottawa Citizen reported as follows: [17] At 0820 last evening Mayor Morris gave the word and the first electric car on the through line between Ottawa and Aylmer via the Interprovincial Bridge started on its way. The first turn of the wheels, the first note in the song of the trolley marked an epoch in the history of Ottawa as a railway centre …George McConnell was the motorman in charge of the car ...regular service will be inaugurated this afternoon.. A twenty minute service will be put on till noon and a fifteen minute service the rest of the day.The bridge featured prominently in the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York in September 1900. It was illuminated from end to end but a few days before the main event there was a severe tornado which passed though the area It had been the plan of Horace Beemer, supported by the mayor of Ottawa, to ask the Duke to name the bridge Royal Alexandra after the Duchess. However, although this name has been used until the present, there is no record that this was actually done and so the use of the name might be considered a violation of protocol. On 2nd December 1901, the Pontiac Pacific Junction opened a curve from the Canadian Pacific Hull station to the Interprovincial Bridge approaches allowing trains from Aylmer to use the bridge.[20] Effective 1st May 1902 Canadian Pacific acquired control of the Ottawa, Northern and Western and on 23rd May ON&W trains were diverted across the Prince of Wales Bridge (i.e. away from the Interprovincial Bridge) into the CPR Union Station at Broad Street (on Lebreton Flats). The CPR transcontinental trains were diverted from the North Shore (now Lachute subdivision) to the Short Line (M and O subdivision) on 15th June 1902 [21]. This very low use of the bridge (i.e. by just the transcontinental trains) was continued until 1917 [22], when it diverted some of its trains into the Central Station, which, in 1921, became known as Union Station. From that time, the Interprovincial Bridge was used by the CPR transcontinental passenger trains and passenger trains to Montreal (via Lachute), Maniwaki (maybe from 1917) and Waltham.

The streetcar service came to an end on 29th March 1946 when fire destroyed the trestle at the north end of the Interprovincial Bridge. The electric cars were turned at the intersection of Laurier Avenue and Youville Street, near the north end of the Interprovincial Bridge, until the system could be formally abandoned by 1st April 1947 [23]. The Canadian Pacific trestle was also damaged by this fire but the railway company quickly rebuilt it and restored railway communication.CP 4-6-2 1261 crossing bridge at St. Etienne Street in Hull on 15th May 1954. The Canadian Pacific Railway passenger trains continued to use the Interprovincial Bridge until the new Ottawa station was opened on 31st July 1966. From that time, all trains between Ottawa and Hull used the Prince of Wales Bridge and the Interprovincial Bridge was converted into a road/pedestrian bridge.

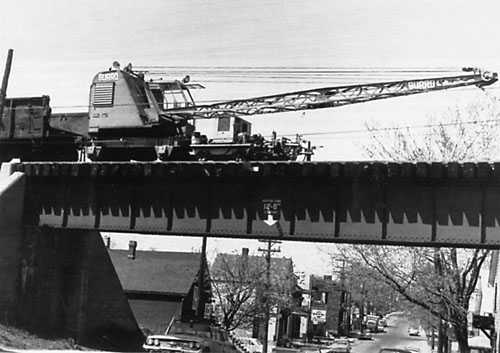

The Greber Plan, published in 1950, which recommended the removal of the down town tracks and elimination of trains from the Interprovincial Bridge, felt it was an eyesore and advocated removal in favour of a bridge further east on the location of the present MacDonald Cartier bridge. The Interprovincial Bridge survived this threat and today provides an essential, and heavily used, link in the local transportation network.Rail mounted Burro crane on the Notre Dame Street overpass in Hull, mile 88.53 of the CPR M&O subdivision. The crane was owned by A.A. Merrilees and was used in the dismantling of the CPR line from Ottawa Union Station, across the Interprovincial Bridge to Hull. Below the bridge can be seen the Merrilees Chevrolet Kingswood HyRail station wagon. This was a model which was only made in the USA and caused a great deal of comment wherever it went. Spring 1967. Conclusion

The Interprovincial Bridge was a remarkable achievement. Pier No.2, if seen on dry land, would be a column 100 feet high. It carries current road traffic even though it was only designed for a live load of two 1900 era 2-8-0 steam engines and train while the roadways were designed for a four car electric train with a total weight of 120,000 lbs. each car having a seven foot wheel base. Road traffic anticipated was entirely horse drawn (the automobile had only appeared on the streets of Ottawa the year before the bridge was opened) and the largest vehicle planned for was a 13 ton road roller. One improvement since the elimination of the railway is the replacement of the original wooden decking with steel. The trains, even diesel hauled, created great vibrations for road traffic and scared many an unsuspecting motorist. One has to think that, had the City Engineer had his way with a fifteen foot screen, not only horses, but many a motorist would have been spooked when the bridge suddenly started to vibrate for no apparent reason! Let us wish the Interprovincial Bridge Many Happy Returns. It has certainly withstood the test of time! Sources Dorman, Robert/Stoltz, D.E. - A Statutory History of Railways in Canada Public Archives - Record Group 12 volume 2506 file 3534-50 Public Archives - Record Group 46 1992-93/066 Box 42 files 41097 and 41097.1 Ottawa Evening Citizen 1901-1902 Discussions with members of the Ottawa Railway History Circle, in particular, David Jeanes and Dennis Peters. Footnotes [1] Orders in Council PC 1897-1548 of 28th June 1897 and PC 1897-1614 of 5th July 1897. [2] Orders in Council PC 1898-436 of 28th February 1898, PC 1898-555 of 14th March 1898 and PC 1899-341 of 2nd March 1899. [3] Order in Council PC 1899-1922 of 28th August 1899. [4] Order in Council PC 1898-555 of 14th March 1898. [5] Railway and Shipping World November 1899 page 326. [6] Railway and Shipping World July 1900 page 195. [7] The investigation into the Cornwall bridge collapse found that the pier was improperly placed on the river bed and there was no question over the quality of the concrete. The Department did not know this when the Interprovincial Bridge was being constructed. [8] Order in Council PC 1900-2484 of 2nd November 1900. [9] Order in Council PC 1900-1875 of 26th July 1900. [10] Order in Council PC 1900-2484 of 2nd November 1900. [11] Ottawa Citizen 5 March 1901, page 3. [12] Railway and Shipping World August 1901 page 229. [13] National Archives RG 43 volume 207 file 560. [14] Ottawa Citizen 23 April 1901. [15] Railway and Shipping World November 1900 page 337. [16] Ottawa Citizen 17 May 1901, page 2. [17] Ottawa Citizen 25 July 1901. [18] Ottawa Citizen 17 September 1901, page 7. [19] Ottawa Citizen 21 September 1901, page 7. [20 National Archives RG 43 volume 211 file 731. [21] Doug Smith Canadian Rail Passenger Review Number 3 article on the Imperial Limited. [22] National Archives RG 46 volume 1575 file 24356.1. [23] Board of Railway Commissioners order 68260 of 6th December 1946 as modified by order 68301 of 13th December 1946. Bytown Railway Society, Branchline, February 2001 |

![]()